Identifying and Implementing Traits of Actionable Racial Allyship in the Workplace at Miami University

Discrimination toward people of color has a deep-seated past in American culture and workplaces, resulting in racial inequality rooted in systemic racism. While it became illegal for employers to discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, some work environments evolved into covert racist practices. This research study explores ways to question institutional processes, systems, and programs to fight systemic racism within the workplace at Miami University. It looks to challenge racial majority employees to examine their privilege by addressing bias, unconscious bias, microaggression, and micro-inequities through modern diversity training techniques. This modern diversity, equity, and inclusion training includes intergroup dialogue, perspective-taking, and goal-setting insights personal reflection. Combining these techniques generates thought-provoking discussions that have the ability to produce personal growth, revising institutional practices, and perpetuate social movement. This study holds significant implications for modern workplace models that wish to create a culture of actionable allyship, address institutional racism, and reduce discrimination. By building empathy toward people of color, work environments can grow into being supportive and inclusive places of opportunities for all.

Introduction

Background

Over the past five years working at the university within two different departments, University Advancement (UA) and University Communications and Marketing (UCM), I have found each department struggles with racial bias, discrimination, and white privilege. Both departments are overwhelmingly white, with a high turnover rate for employees of color. To give context, for the entire university, 18.6% of faculty and 10% of staff are racially diverse, and the student population is 15.6% racially diverse (Data, Reports, and Demographics, 2019). A former employee of color stated, “Once I started my position in UA, I immediately started looking for a new job. I quickly found that I was the only person of color in a department of 125. Leadership was unwilling to address the hostile work environment and were not open to constructive feedback to create positive social change.” Raising awareness of issues experienced by marginalized people needs to be encouraged and addressed wholeheartedly. Blaming the person for calling attention to the issue rather than fixing it is a characteristic of white supremacy culture (Jones & Okun, 2001). Though the university requires faculty to participate in bias training, it is not a requirement for staff. With an overwhelmingly white population, the university needs to make significant changes to evolve the institutional culture, develop empathy and adapt to the modern understanding of inclusivity.

After the public slaying of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, MN, on March 25, 2020, conversations about systematic racism and social justice filled my workplace in UCM. The white employees looked for the few employees of color to lead the conversations about race and white privilege. These actions made me wonder, how can the script be flipped, and how can we educate the white majority about race, discrimination, and privilege in a safe environment? How can individuals make real change and the privileged majority be responsible for closing the gap of race inequality—instead of the burden to educate and foster change falling onto the shoulders of people of color?

This research study explores ways to challenge institutional processes, systems, and programs to fight systemic racism within the workplace at Miami University. It will also look to challenge racial majority employees to examine their privilege by addressing bias, unconscious bias, microaggression, and micro-inequities in the workplace. I hope to challenge white people to develop a deeper understanding of allyship toward oppressed or marginalized groups and positively impact their work environment by being more inclusive.

Problem Statement

Racial equality has made strides since the Civil Rights movement, but people of color continue to experience discrimination, prejudice, and systemic racism. The Civil Rights Act in 1964 made it illegal for employers to discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Though blatant discrimination has been outlawed, people of color still encounter biases and discrimination, often even before they are hired and simply based on their names. People with white-sounding names are 50% more likely to receive interview callbacks than those with traditionally Black names (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). When hired, people of color earn less than their white male counterparts—black men 87 cents for every dollar, Hispanic and Native American men 91, and Pacific Islander 95 (Miller, 2020). The pay gap reinforces that businesses and society value people of color as less than the white majority, making it almost impossible for underrepresented people to move up in socioeconomic class and continuing the cycle of inequality.

Purpose of Study

The purpose of the study aims to identify and implement traits of actionable racial allyship at Miami University to create an inclusive, safe work environment.

Research Question

How can a culture of allyship be introduced to make an inclusive work environment at Miami University?

Significance of the Study

Miami University is a more than 200-year-old institution in southwestern Ohio with a history of cultural appropriation, cultural racism, and prejudice. The university takes its name from the Myaamia, a sovereign nation recognized by the United States of America as the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma (Weingartner, 2020). The university did not consult the tribe to receive approval of the name or racially insensitive mascot usage. It was not until 1972 when Chief Forest Olds of the Miami Tribe heard that a university shared the same name as his nation (Weingartner, 2020). Chief Forest Olds then visited the university, and the relationship with the Miami Tribe began. In 1990, the relationship evolved into focusing on the education of Miami University students about what it means to be a Native American Tribe in the United States, and the first Miami Tribe member enrolled at the university (History of the Relationship between Miami and Tribe, 2020). With a new connection with the Miami Tribe, the university leaders gained a new perspective and understanding of the Miami Tribe. In 1996, the Miami Tribe requested the university drop the race-based nickname and mascot because it is now considered a slur by the Miami Tribe, Miami University, and society-at-large (Weingartner, 2020).

Over 25 years after changing the mascot to “RedHawks,” some alumni remain upset about the change and vocal about their disapproval. Posts on the Miami University social media accounts often receive comments such as, “I will always be a *******,” “Like it or not, I will always be a *******,” “Love and Honor from a former *******.” Alumni take pride in their Miami University education and college experiences, though this pride is deeply connected to a problematic mascot that objectified the Miami Tribe’s culture.

Discrimination and hate speech toward people of color persists as a common experience at Miami University. A group of students became frustrated with the university’s inaction and created an Instagram account named “Dear Miami U” on June 28, 2020. The account was created to share stories of discrimination against marginalized students at Miami University. One of the posts reads, “I’m an Asian American who recently graduated from Miami University. Every time I went out on the weekend, I was approached by individuals who asked how I was so fluent in English and if I would teach them Chinese swear words so they can say them to the international students. Other students would exclude me from group projects, thinking I couldn’t speak English or wouldn’t participate. Staff members would tell me to tell my Chinese friends to stop speaking Chinese while they’re in America. A group of frat guys approached me one night, spit on the ground in front of me, and called me a “*****.” During my four years, I spent every day feeling less confident, motivated, and hoping for change that never happened” (Dear Miami, Here Are Our Stories). As of March 12, 2021, 774 stories have been shared with the “Dear Miami U” community. University administration has yet to address the account or stories posted, affirming the university’s inaction and suggesting avoidance and tolerance of hatred.

This study holds significant implications for modern workplace models that wish to include actionable allyship, address institutional racism, and reduce discrimination. 2020 was an unprecedented year with the world in the midst of a pandemic and the increased momentum of the BLM movement, and America was forced to confront racism while reconciling the past and the present (Chavez, 2020). In late December 2019, the first case of SARS-CoV-2, or COVID-19, was detected in Wuhan, China. Later, the United States’ first case was confirmed on January 21, 2020, which began the global lockdowns. It was not until March 11 that COVID-19 was declared as a global pandemic. Days later, President of the United States Donald Trump tweeted about the “Chinese virus”(Salcedo, 2021). This comment likely accelerated Xenophobic comments and attacks toward Asian Americans, blaming them for the global pandemic.

With the world shut down from the pandemic, stories of racism and police brutality toward Black and African Americans flooded social media, news channels, and interpersonal communications. The deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd shook the country, bringing conversations of race, police brutality, and inequality to the forefront, resulting in worldwide protests and support of the BLM movement. Understanding the forms of discrimination and bias people of color experience within the workplace informs what needs to change to foster an inclusive work culture while addressing white privilege and white supremacy culture.

Methodology

This research was conducted under the direction of Critical Theory and Black Feminists Thought. These theories challenge the current workplace culture, structure, and cultural assumptions toward minority groups based on race and ethnicity and fighting institutionalized racism, social, and economic injustice. Conducting interviews and co-design sessions allows people of color to share their experiences of institutional racism, discrimination, and injustice, have their concerns and needs to be heard, and then incorporate that information in the design solution.

This research study used qualitative research to gather general thoughts of the current climate on racial discrimination in the workplace at Miami University through surveys and personal views and experiences through surveys, interviews, and co-design.

- Survey – was designed to build a greater understanding of the Miami University employee opinions, viewpoints, and experiences with diversity and inclusion, racial injustice, and allyship. The survey consisted of 25 multiple choice and open-ended questions. A stratified sampling of Oxford campus employees was provided from the Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness and recruited participants by their email addresses.

- Interviews – were conducted using Google Hangout. A stratified sample of Miami University Oxford employees were recruited to participate. The interview consisted of 22 open-ended questions that averaged 45 minutes to complete. The interview script was developed to encourage an in-depth conversation about racial inequality, discrimination, allyship, and the university’s commitment to diversity and inclusion.

- Co-design – is the process where designers and non-designers work together in the design development process. This process flips the typical role of the research and person who will be served by giving the person being served the position of being the expert of their experience, playing a role of knowledge development, idea generation, and concept development (Sanders & Stappers, 2018, p. 24-25). These co-design sessions included the use of the “make” method. The “make” method allows people to express their thoughts and feelings through a carefully developed toolkit (Sanders & Stappers, 2018, p. 70), allowing for qualitative results. Make sessions give participants the ability to express in different ways to recall memories and interpreting emotions.

Findings and Results

The results of this study revealed that participants felt that the university, colleagues, and community members do not recognize the extent of discrimination that people of color experience within the workplace. The qualitative data created a broad overview of their general views and also provided insight into personal experiences. Three themes emerged, which all pointed to the need for education, training, and change, which will be used to inform possible design interventions. The three major themes are:

- Building social justice,

- Current institutional culture,

- And the opportunity for personal and institutional growth.

Employees of color said there is a need for continued learning and communication about racial discrimination and oppression, no matter their racial identity or ethnicity. They expressed that there is an opportunity for employees to unpack their privilege based on their race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or physical ability. All cultures should be considered in the workplace—not just those based on the white majority—to create an inclusive environment. They stated that the university and their coworkers need to work on building racial equality and support.

For years, employees of color have felt misunderstood and that they are being used to fill a diversity quota. The hostile work environment and negative institutional support have made it difficult to recommend other people of color to work or attend the university. Multiple departments, divisions, or offices have started their own diversity programs, initiatives, or task forces. While leadership intends these initiatives to be positive departmental and divisional support, the efforts lack a centralized message or direction from university leadership. Based on slow and problematic responses to racism and oppression experienced by students and employees, employees of color believe there is a need for institutional change. Measurable change can begin when the university listens to the needs of workers, supports marginalized communities, and creates a better education or system of training for all employees.

Employees of color communicated that the university as a whole has a long way to go in terms of racial bias and discrimination. They feel that the university lacks diverse representation in leadership, faculty, and staff, and would like to see an investment in the recruitment, retention, and mentoring of employees of color.

Design Intervention

Over the years, diversity training has received a bad reputation for being preformative. However, research shows that over 40 years of diversity training evaluations diversity training can work, especially when it targets awareness and skill development and occurs over a significant amount of time (Lindsey, King, Membere, & Cheung, 2017). Based on primary and secondary research findings, I was led to explore design concepts related to fostering empathy and education about race through intergroup dialogue, perspective-taking, and goal setting. Based on the structure of the prototype and the use of the perspective-taking technique, the test encouraged dialogue and sharing of perspectives, experiences, and emotions. The intervention’s learning goals were based on Bloom’s Taxonomy framework which consists of six major categories: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Armstrong, 2010). This framework believes knowledge and understanding is necessary for putting learned skills and abilities into practice.

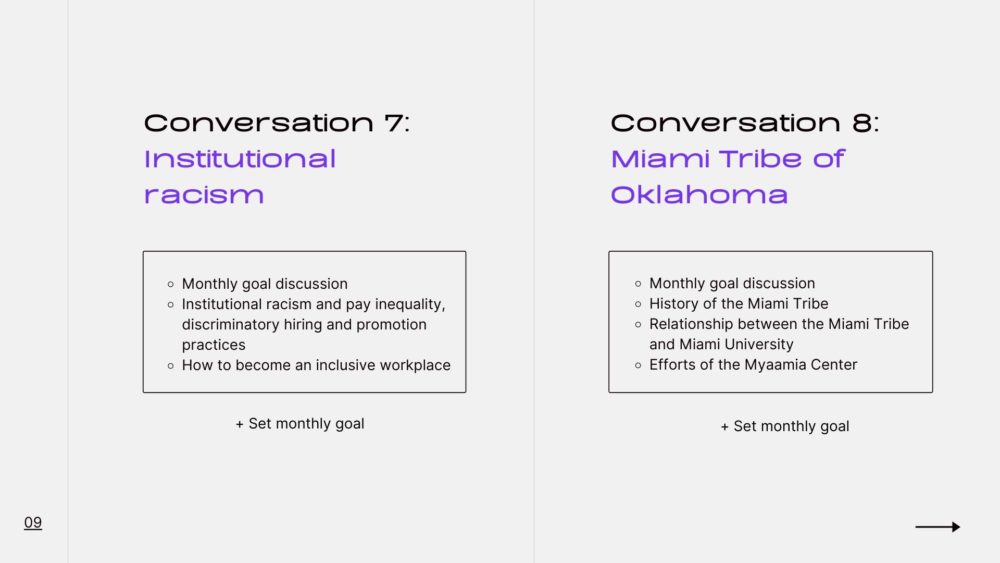

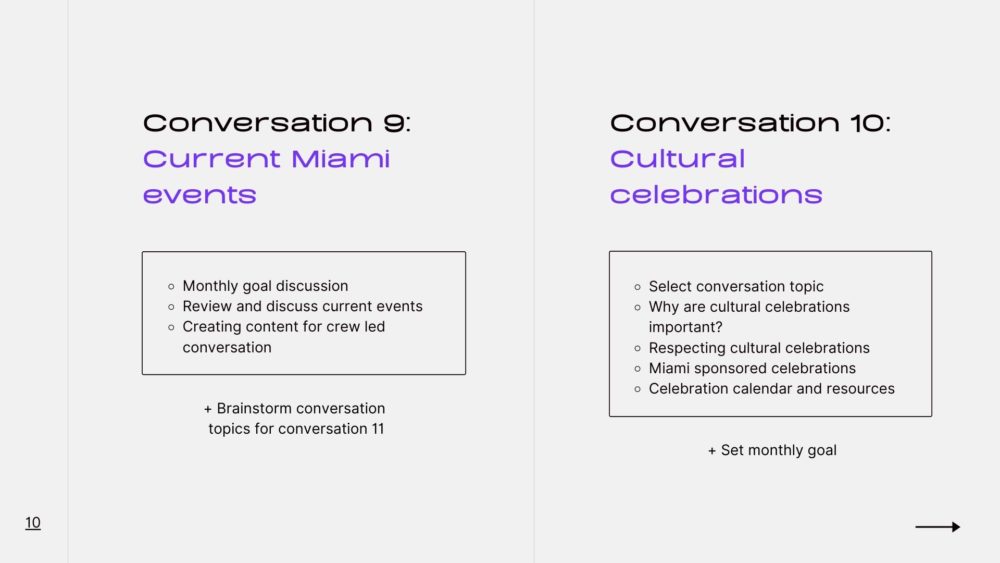

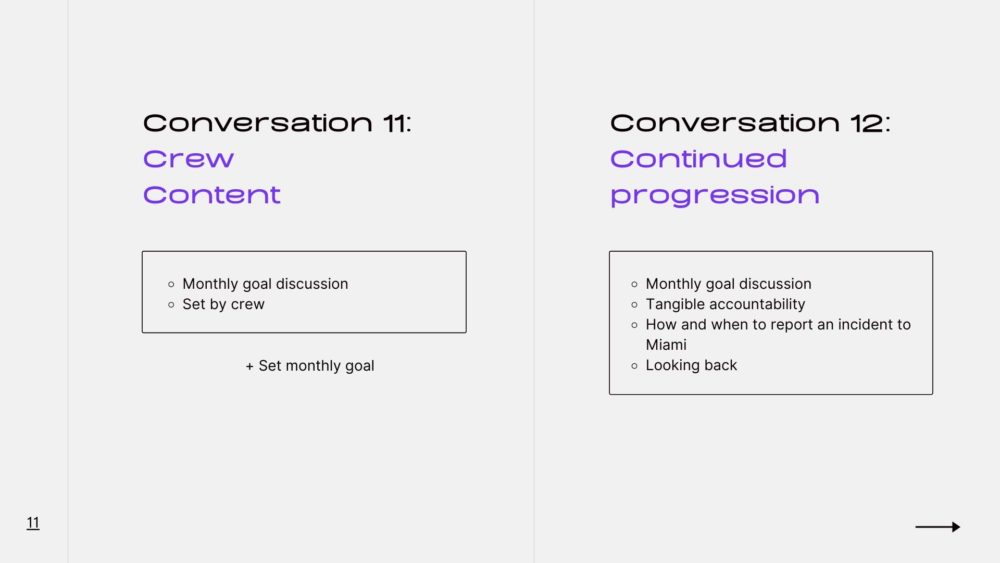

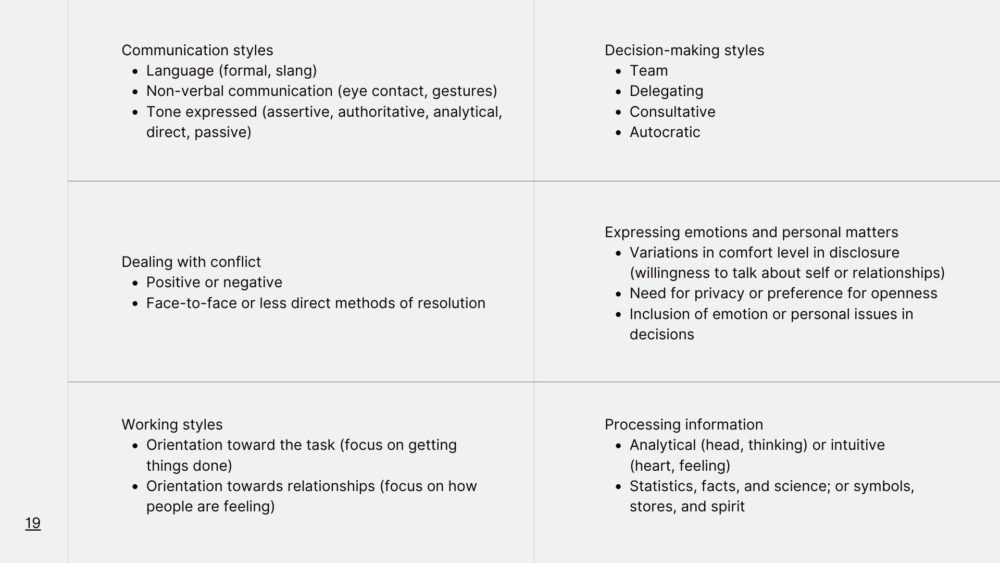

Cultural Conversations

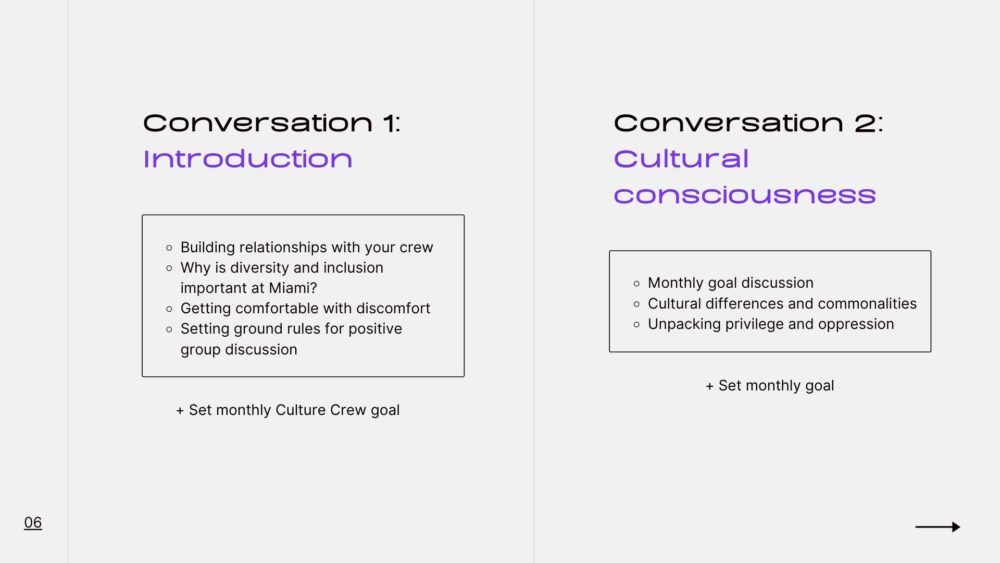

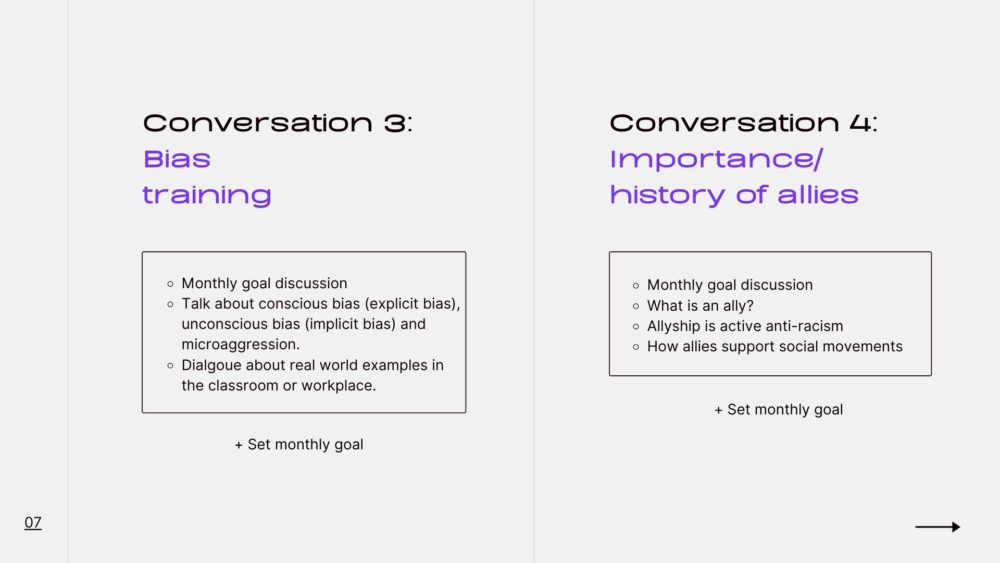

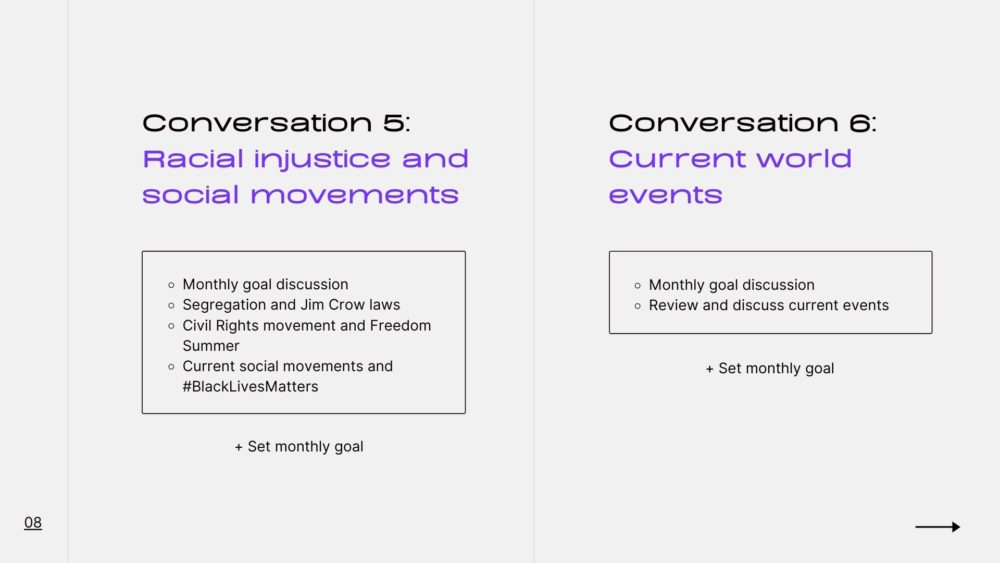

The diversity program developed for this research, “Cultural Conversations,” is a program that is guided by a trained employee leader that follows a templated lesson plan to educate employees on how to be culturally conscious. This model uses intergroup dialogue, perspective-taking, and goal-setting techniques to prompt participants to imagine themselves in another person’s shoes, listen to others’ experiences, and establish empathy toward others, with the goal for this program to be a meaningful and lasting learning experience. Conversations range in topics such as cultural consciousness, bias training, importance and history of allies, racial injustice and social movements, current world events, institutional racism, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, current Miami Events, cultural celebrations, and continued progression.

“Cultural Conversations” is a 12-month employee-required program to encourage conversations about race, culture, and inequality in a safe and controlled environment. Because all employees are brand ambassadors, this required program will prepare them to be culturally conscious colleagues, leaders, and global citizens. Employees will be divided into a “Culture Crew” consisting of 8-10 people from across campus.

A trained volunteer leader, known as a “Culture Captain,” will facilitate the monthly Cultural Conversation. Each “Culture Crew” is a stratified sample of employees, classified, unclassified staff, and faculty. The stratified sampling will ensure diversity of race, ethnicity, and background among “Culture Crew” members. Any employees hired after the launch of Cultural Conversations will be assigned a “Culture Crew” quarterly. The Cultural Conversations team is located within the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, which conducts “Culture Captain” training, assigns employees to “Culture Crews”, conducts participant surveys and addresses any concerns with “Culture Captains”.

The “Culture Captains” are certified employees recruited across campus to guide “Culture Crews” in their culturally conscious journey. University employees will be notified of the opportunity to become a “Culture Captain” through a university-wide email and post on MyMiami, the university’s employee portal. Employees who express interest in becoming a “Culture Captain” will be required to participate in a five-day training on the university’s “Cultural Conversations” initiative. Once they have completed the required training, the title “Culture Captain” will be added to their job title and responsibilities, to ensure this important activity is adapted to their current workload. In return for their leadership and time commitment, Captains will receive professional development funds from the university for training and subsequent sessions.

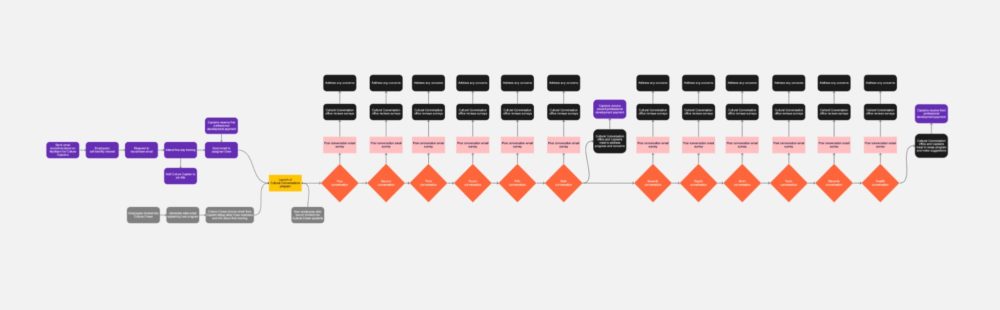

The user flow and logistical process is visually explained below.

During the sessions, participants will be given the option to complete a survey to give feedback on the program and Captains, to ensure they are effectively leading and providing a safe environment. If there is any misconduct, participants can report an incident by online form or in person.

Below is the overview presentation of the program.

Design Intervention Development Process

This intervention was directed by existing research and techniques. Research on intergroup dialogue (IGD) shows that technique fosters honest and educational dialogue to build an understanding of people from different backgrounds. These dialogues began with socio-political issues such as the Civil Rights Movement, the Peace Movement, the Feminist Movement, the Gay Rights Movement, and the Disability Rights Movement (Maxwell, K. & Thompson, M, 2017). The IGD technique has been adapted to promoting understanding of racial inequality and oppression within workplaces. Within group discussions, participants are enabled to explore their social identities and critically examine structural inequities, develop meaningful cross-identity relationships, and apply content and process learning to promote alliance building and social action (Ford, 2018). IGD has been proven to work based on a multi-university study (Gurin, Nagda, & Zúñiga, 2013), where data indicated a number of attitudinal and behavioral changes in participants, including increased self-reflexivity about issues of power and privilege, heightened awareness of the institutionalization of race and racism in the U.S., improved cross-racial interaction, diminished fear about race-related conflict, and increased participation in social change actions during and after college (Ford, 2018). This previous research and proven results were instrumental while developing a solution that could make an impact at MU.

Research has found that perspective-taking has been a successful technique to build empathy toward people of other cultures and backgrounds. One study had participants write a few sentences imagining the challenges marginalized members might face. Results found that participants had an improved pro-diversity attitude and behavioral intentions toward people of different backgrounds and cultures (Lindsey, King, Membere, & Cheung, 2017). These results indicated that the perspective-taking technique, combined with IGD, would foster positive conversations about challenges and assumptions.

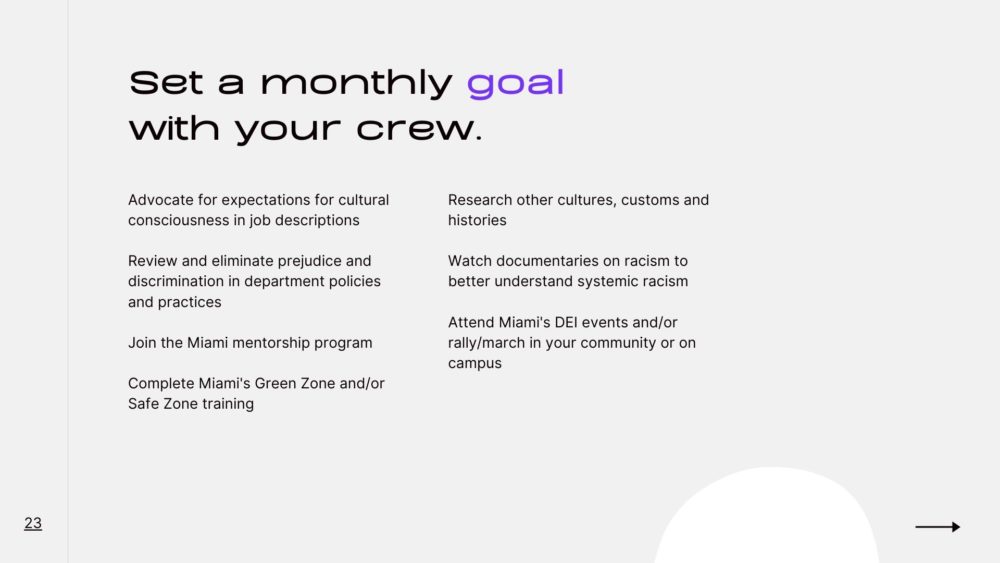

Lastly, adding a goal-setting element into diversity training creates an opportunity for lasting or increased information retention after training sessions have concluded (Latham, 1997). Goals have been found to have a positive effect on people by driving motivation and guiding behavior (Locke and Latham 1990). This information has led me to believe that setting a collective group goal would likely build understanding and bond between participants when creating shared or similar experiences.

Testing

The prototype, Cultural Conversations, was guided by Bloom’s Taxonomy framework to test the learning of the focus group. The three participants began by completing a pre-training audit, gauging their own cultural competency.

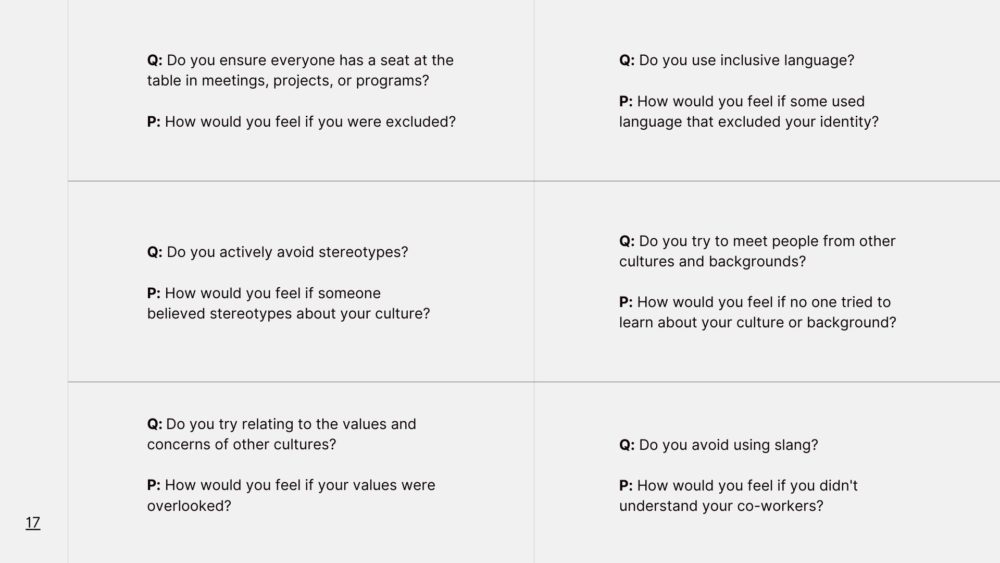

After completing the audit, the sessions begin with a short lesson and progress into a guided group discussion. Members were asked questions about cultural consciousness and then prompted to think how they would feel in someone else’s shoes.

At the end of the session, crew members determined a collective goal for every member to focus on until the next meeting. The goal will be the same for each member but can be done individually. At the beginning of the next conversation, team members will dialogue and reflect on similar or different experiences, hopefully leading to increased allyship and desire to affect social change.

Results

The findings of the focus group indicated that participants self-identified as more culturally conscious after completing the sample training. The following themes emerged from the conversation from the focus group:

- Clique Culture – the Miami work culture operates like a clique; participants are excluded because they are not in the “popular” group. The group often makes decisions based on conversations that not everyone was included in. Participants are so used to not being included they do not even necessarily think about it as a slight, but there are unintended consequences or unconscious bias that might be behind the action.

- Trying to be inclusive allies – participants shared that they have tried their best to be inclusive, and when they make a mistake they learn from the situation. They also know that everyone makes mistakes, and appreciate when colleagues stop and correct themselves or later apologize for their comments or actions. It shows that their colleagues are trying to be more culturally aware and make people feel comfortable in the workplace.

- Assumptions leading to strife – Religious and cultural assumptions have led participants to struggle with being excluded. Their work environments have made them feel ignored or less than other colleagues.

Based on the conversations within the focus group, participants gained understanding or saw situations in a new perspective. They were able to empathize with each other and build conversations from the prompts. From on the results of pre and post self audits slightly improved their understanding of cultural consciousness or realized that they are doing a better job than they originally thought.

Through IGD, perspective-taking, and goal setting, participants were able to empathize and hear about other experiences from across campus. Hearing from employees from across the university brought to light the common struggles divisions, departments, and offices experience as well as, building new relationships with employees from other parts of the university.

Conclusions

This research revealed the current workplace culture, oppressions that employees of color face, and the need for a culture of allyship at Miami University. The findings of this study could be applied to other higher education institutions to improve workplace culture for underrepresented populations.

The findings of this research project revealed the following:

- The work culture at Miami University perpetuates inequality, exclusion, and a hostile work environment.

- Employees of color want colleagues and university leadership to recognize that race is an issue.

- Employees want better and timely communication from the university leadership when issues arise.

- There needs to be a centralized message, direction from university leadership, and an unified training program.

- Participants want the University to educate students and all employees about race issues.

- White employees feel they do not know enough to engage in discussions about racial injustice effectively.

- Allies are essential and have played crucial roles in past and current social movements.

- Participants want the University to help facilitate discussions, share educational resources, offer training, etc., and more accessible resources available to faculty and staff.

- Intergroup dialogue, perspective-taking, and goal setting effectively made an impact on participants’ understanding of cultural consciousness.

Research shows that systemic oppression can not be dismantled just by the oppressed but requires support, education, and action from allies. Since many white people feel that they do not know enough to engage in discussions about racial injustice, it is essential to create an education program in the workplace. Based on the importance and sensitivity of the topic, innovative and modern techniques have to be used to make a lasting impact.

Suggestions for Future Research

Further research is necessary to replicate and expand on the findings of this study. A larger and more accurate representation of the university employees’ would allow for a deeper understanding of issues or struggles that could arise in the “Cultural Conversations” program.

Further development of the courses is needed to test a full cohort of employees. As current events happen, it is important to regularly add topics of discussion to ensure the best possible learning.

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013. doi:10.1257/0002828042002561

Chavez, Nicole. (2020). “The Year America Confronted Racism.” CNN, Cable News Network, www.cnn.com/interactive/2020/12/us/america-racism-2020/.

“Data, Reports, and Demographics.” (2019) Data, Reports, and Demographics | Diversity and Inclusion – Miami University, www.miamioh.edu/diversity-inclusion/data-reports.

“Dear Miami, Here Are Our Stories.” Google Sheets, Google, docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Uh9NR4NOreO_PmefS0Jp5Oa0hXZa2Fe2vbFa-iuKTKk/edit#gid=254829468.

“DEI Task Force Recommendations Overview.” (2020). Overview | DEI Task Force Recommendations | Diversity and Inclusion – Miami University, www.miamioh.edu/diversity-inclusion/data-reports/dei-task-force-recommendations/overview/index.html.

Ford, K. A. (2018). Facilitating change through intergroup dialogue: Social justice advocacy in practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., & Zúñiga, X. (Eds.). (2013). Dialogue Across Difference: Practice, Theory, and Research on Intergroup Dialogue. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

“History of the Relationship between Miami and Tribe.” (2020, August) Narration by Chief Douglas Lankford, and Bobbe Burke, Miami University, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozYKowCNNYE.

Jain-Link, P., Kennedy, J. T., & Bourgeois, T. (2020, January 13). 5 strategies for creating an inclusive workplace.https://hbr.org/2020/01/5-strategies-for-creating-an-inclusive-workplace.

Jones, K., & Okun, T. (2001). Dismantling Racism: a Workbook for Social Change Groups. ChangeWork.

Latham, G. P. (1997). Overcoming mental models that limit research on transfer of training in organizational settings. Applied Psychology, 46, 371–375.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Lindsey, A., King, E., Membere, A., & Cheung, H. (2017, July). “Two Types of Diversity Training That Really Work.” Harvard Business Review, 2hbr.org/2017/07/two-types-of-diversity-training-that-really-work.

Maxwell, K. & Thompson, M. (2017). Breaking Ground Through Intergroup Education — The Program on Intergroup Relations (IGR) 1988-2016. 1st ed. [ebook] Ann Arbor. Available at: <https://drive.google.com/file/d/14NDSVyIRerjEMUPln7BIjFIiIKZS9Ley/view>.

Miller, S. (2020, August 7). “Black Workers Still Earn Less than Their White Counterparts.” www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/compensation/pages/racial-wage-gaps-persistence-poses-challenge.aspx.

Salcedo, A. (2021, March 19). “Racist Anti-Asian Hashtags Spiked after Trump First Tweeted ‘Chinese Virus,’ Study Finds.” The Washington Post, WP Company, www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/03/19/trump-tweets-chinese-virus-racist/.

Sanders, E., & Pieter, J. (2018). Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. BIS Publishers

Weingartner, T. (2020, July). “Miami U Dropped Its Race-Based Mascot 20 Years Ago, Sees Benefits Today.” WOSU Radio, July 2020, radio.wosu.org/post/miami-u-dropped-its-race-based-mascot-20-years-ago-sees-benefits-today?fbclid=IwAR2TMn9Ku4S7jI1fe0wiIYuQe_C0KwFSbfPoC-TJTUahGFn22H39Zvfl0b8#stream.

Full Thesis Document

OhioLINK Acces

xdMFA Candidates must disseminate their research online in the Ohio Library and Information Network (OhioLINK) Electronic Theses and Dissertations repository. This thesis may be accessed at

http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=miami1619122995812556