Codesigning a Physical Thirdspace in a Digital Setting for a Reimagined Community

This research project examined values related to interaction, inclusion, and belonging shared among the people of Traverse City, Michigan. It integrated experience design and critical geography, a critical theory-based framework. Three major themes emerged from this project: transformative placemaking, thirdspace, and codesign. These themes provide insights and practical ways for communities to expand access through tactical and creative actions. First, this project focused on the transformative power of placemaking as both an ideology and a practice. Second, the concept of thirdspace exemplifies how placemaking can transform communities by empowering people to work together toward collective wellbeing. Third, codesign puts the power to design in the hands of a project’s stakeholders to shape their own experience. This project’s mixed-methods approach answered the primary research question, “What kind of thirdspace design would be meaningful and relevant for residents of and returning visitors to the Traverse City, Michigan, region in a way that facilitates belonging?” Findings are discussed in six thematic groupings, which directly informed the design intervention—the Make a Thirdspace toolkit that stakeholders may use to codesign their own thirdspace. This project invites future investigations into the values and needs that drive communities to reimagine themselves through equitable and revitalizing partnerships.

Introduction

Background and Problem Statement

The German word Heimat—translated most simply as “home”—encapsulates a range of emotions triggered by the powerful archetype it conveys. Feelings of belonging, inclusion, and relatedness drive decisions about where to live and work, how and with whom to spend time (Lewis et al., 2000). But what the German Heimat captures that the English equivalent does not is the social dimension of feeling at home. Although more commonly associated with the love people feel for their country (the “homeland”), Heimat can also be understood as any place where, together, people feel like they belong.

Local communities need such places to thrive. People need options and opportunities to gather in a public space other than the home or the workplace. We need venues that facilitate planning, organizing, creating, and collaborating (Vey, 2018). These places include bookstores, cafés, coffee shops, libraries, pubs, public parks, bike hubs, and community gardens. But for various reasons (economic, technological, and ecological, to name a few), such places are hard to build and sustain. One community that has rooted itself in public gathering places is Traverse City, Michigan—a “charming” (Top 10, 2010) small town in Northern Michigan that boasts 180 miles of beaches and large-scale production of tart cherries and grapes. Not just a premier travel destination in the Midwest, Traverse City is home to more than 15,000 residents, many of whom have multigenerational ties to the region. This mix of residents and visitors uniquely defines the city and surrounding area, whose identity has shape-shifted over time to align with an ever-evolving group of community stakeholders.

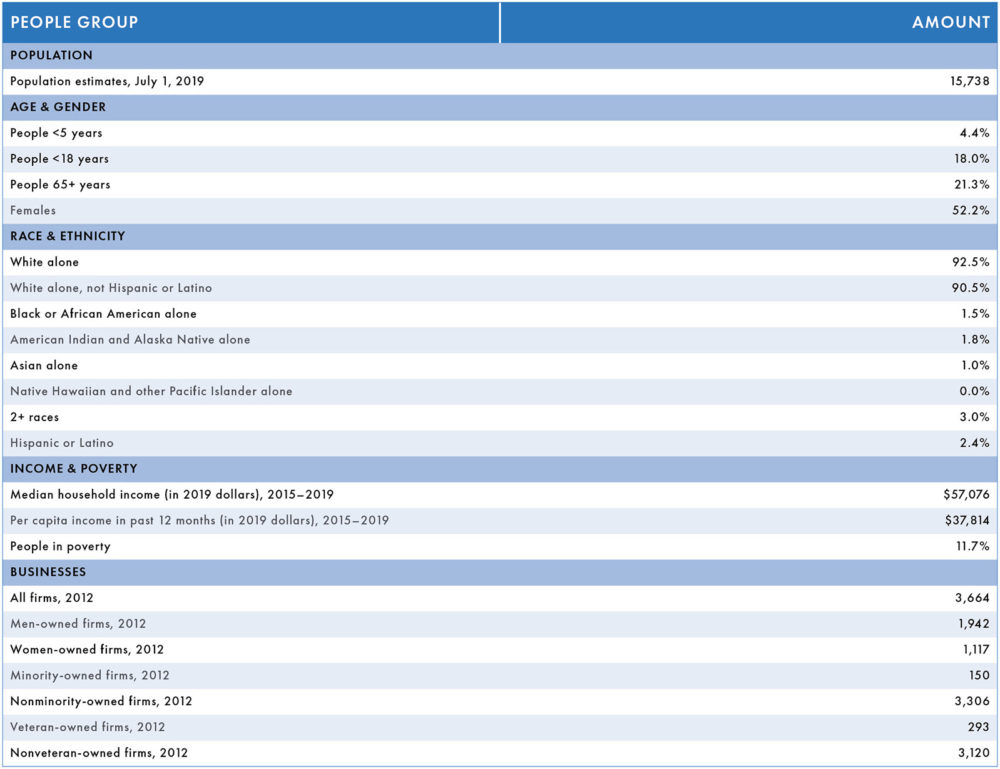

Traverse City’s demographic makeup, as reflected in this table, is not particularly diverse, especially when compared with the demographics of neighboring Grand Rapids (a city nearly 13 times more populated than Traverse City).

Nonetheless, the U.S. Census data collected in this table highlight the underrepresented groups in Traverse City (including the poor, nearly 12% of the population, and people of color, less than 10% of the population) whose unique needs and challenges are crucial to factor into any community-based undertaking. Representing the underrepresented becomes even more important in communities where less powerful and powerless voices, who comprise a small but significant part of the population, are drowned out by those in power, or the overwhelming majority—in this case, white middle-class residents (Costanza-Chock, 2020).

Representing the underrepresented becomes even more important in communities where less powerful and powerless voices are drowned out by those in power.

The Traverse City region faces unique economic challenges—challenges that have only escalated during the coronavirus pandemic—due to its distinctive demographic makeup. Specifically, increasing numbers of retirees and decreasing numbers of young workers and families compound the problems characteristic of resort destinations like Traverse City—especially low wages and high living costs (Milligan, 2019). These conditions have prompted some wealthy residents (like Traverse City Film Festival founder Michael Moore as well as other noncelebrities) to initiate grassroots movements aimed at advancing equity. Additionally, expanding economic opportunities for Traverse City residents and businesses is a focal point for local organizations like the Traverse City Downtown Development Authority (DDA).

Traverse City stakeholders, ranging from ordinary citizens to small business owners to celebrity activists, are passionate about preserving the region’s natural resources—especially its freshwater—which increasingly face threats from environmental crisis and overcrowding due to tourism, among other factors. Numerous conservation efforts are currently underway in the region, including efforts by Nature Change and other local organizations seeking to raise awareness about dwindling resources, invasive species, and climate change.

Traverse City stakeholders are passionate about preserving the region’s natural resources.

In addition to these environmental initiatives, several stakeholders with commercial interests have worked to responsibly develop Traverse City’s production and consumption of goods and services. A small town committed to small business, Traverse City is home to Horizon Books, an independent bookstore operating for nearly 60 years as a downtown mainstay. But Horizon is more than just a bookstore. With its tagline “Find your place,” Horizon is a public gathering place where people convene to escape, socialize, discover, and create. Horizon occupies a massive 22,000-square-foot space, spread out across three levels, each with its own features, furniture, and amenities to encourage different types of activities (quiet reading, performing or watching performances, and drinking coffee, for example). Despite its prominent presence, the bookstore is nestled alongside other local shops and restaurants on pedestrian-friendly Front Street.

In January 2020, just weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we know it, Horizon co-owners Amy Reynolds and Vic Herman announced they would soon close the store because, for a range of reasons, running the business was no longer feasible for the couple. The community was devastated by this news and immediately responded via social media, letters, and interviews with local reporters: there had to be another way. After all, Horizon has for years given Traverse City residents and visitors a sense of belonging, no matter where they are from or how long they stay.

Belonging is a nebulous concept (Allen, 2021) that, for the purpose of this project, means the perception of feeling welcome or at home, so to speak, in a particular setting. In this sense, belonging is inherently place based. For example, four Traverse City women who comprised the longstanding social group known as the Horizon Bridge Club were crushed to learn that their home base would soon be gone—and with it, their identity (Allen, 2021). One group member lamented, “Now we’re going to have to change our name” (as cited in Link, 2020). To some people, the loss of a public gathering place like Horizon spells the loss of self, home, and family. This estrangement, or threat of estrangement, drives some to join forces and work to protect and preserve what is theirs, collectively. But despite our best intentions, designers and ordinary citizens alike often encounter roadblocks, and progress is frequently stalled or even reversed.

To some people, the loss of a public gathering place like Horizon Books spells the loss of self, home, and family.

Overwhelmed by the community’s emotional outpouring, Reynolds and Herman decided to postpone the store closing while they partnered with the DDA and Rotary to explore alternative uses for the Horizon space.

As of this writing, more than a year after Horizon announced its initial plan to shut down, the bookstore is still in limbo as the pandemic rages on. Although Horizon’s fate is unknown, this particular case shows just how critical public gathering places are to the health and wellbeing of communities. The intensely emotional response triggered by the threat of losing such places revealed the value people attach to them. As we are reminded in other social and political contexts—including the storming of the U.S. Capitol in January 2021—public places can achieve sacred status that may become apparent only after this status is challenged (Crosbie, 2021). In this sense, Horizon serves as an example to Traverse City stakeholders that our community is both fragile and resilient, as it is deeply connected to the places that define it (VanderMeulen, 2011).

The intensely emotional response triggered by the threat of losing such places revealed the value people attach to them.

This project took a transformative approach to the universal need for belonging. That is, the participatory design research that underpins this project sought to “change lives of the participants, the institutions in which individuals work or live, and the researcher’s life” (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p. 9; Sanders, 2008). In its focus on the relationship between belonging and setting (Allen, 2021), this project examined the situational knowledge of participants (Traverse City residents and returning visitors) and foregrounded their experience in transformative placemaking and community building. It investigated the function of local and physical public places in nurturing and revitalizing the communities of which they are a part.

Purpose

The purpose of this project was twofold:

- Understand what various Traverse City stakeholders value about physical thirdspaces

- Design an intervention that equips Traverse City stakeholders with tools to create their own solution to the problem they face (needing a public place where they feel like they belong)

Research Question

What kind of thirdspace design would be meaningful and relevant for residents of and returning visitors to the Traverse City, Michigan, region in a way that facilitates belonging?

Methodology

This project’s research design used a mixed-methods approach to collect both qualitative and quantitative data that were then triangulated, analyzed, and coded to discover overarching themes and patterns. Four data collection methods were selected:

- An informal interview was conducted with a Horizon Books co-owner. This conversation developed organically without following a script.

- A survey consisting of 23 questions investigated the 42 participants’ current views of and experiences with thirdspaces. The survey’s open-ended and closed-ended questions were designed to gather relevant data that would supplement the data gathered from the design charrette.

- The participatory, design-led (Sanders, 2008) codesign method of the design charrette (defined for participants as a collaborative workshop) empowered the six participants to apply their expertise as community stakeholders to the process of prototyping an ideal thirdspace.

- A usability test was conducted with three of the six design charrette participants. The test generated practical data about usability limitations of the design prototype as well as qualitative data about participant needs and expectations.

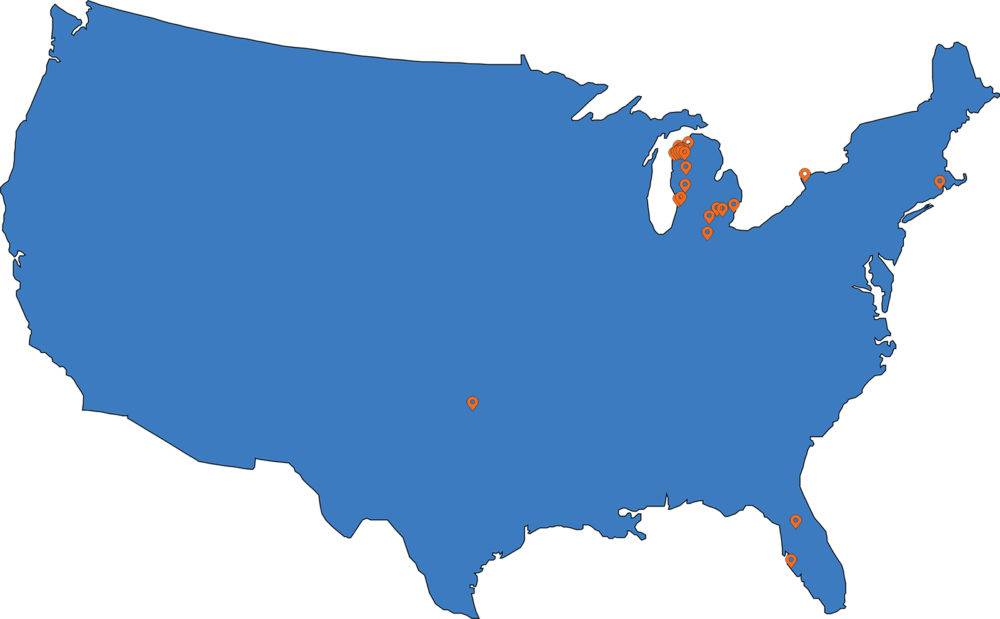

A survey question asked participants to state their zip code, aligning responses with particular geographical locations. About 67% of participants gave a zip code in the Traverse City region with the other 33% scattered around the country but mostly clustered in Michigan. This question is one of several survey questions designed to gather relevant demographic data about participants. These data were analyzed alongside other, more substantive survey responses as well as the collaborative work produced in the design charrette.

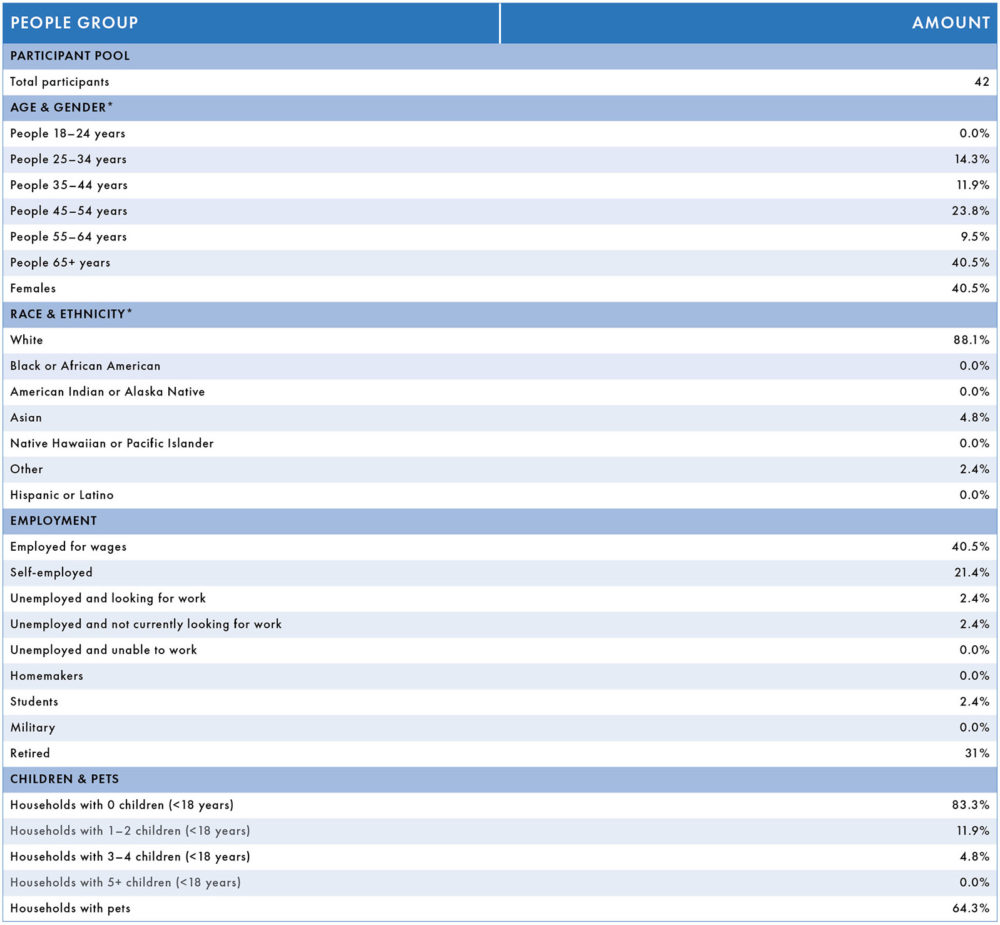

*In response to questions asking about gender, race, and ethnicity, 2.4%, 4.8%, and 12.2% of survey participants, respectively, said they preferred not to answer.

Phenomena Research Results and Findings

This project interpreted and applied data gathered from an informal interview, a survey with 42 participants, a design charrette with six participants, and a usability test with three participants. The narrow scope of the research and the relatively small sample size due to time and resource constraints limited the relevance of this project’s results and findings. Additionally, the situational knowledge of any local population is of limited use for other community-based design projects (Norman & Spencer, 2019). Nonetheless, this project offers a glimpse into some of the challenges and opportunities community members face as they collaborate in thirdspace settings to foster a sense of belonging for more people.

Building from the Ground Up

Survey question 2 defined the concept of a thirdspace as a public place (inside or out, institutional or commercial, physical or digital) where community members feel like they belong. About 71% of respondents said they are familiar with this concept. Survey questions 4–10 went on to inquire about participant experiences with thirdspaces. About 71% reported having frequented a thirdspace, with the majority (60%) of respondents reporting regular visits to a thirdspace. In response to question 5, respondents named a range of thirdspaces they frequented, including bookstores (about 37% named Horizon Books specifically), libraries, museums, coworking spaces, education centers, music venues, art centers, recreation and community centers, coffee and tea shops, pubs, public parks, open spaces, bike hubs, community gardens, and food co-ops. About 77% of respondents felt a sense of belonging in the thirdspaces they frequented, and about 83% of respondents identified social interaction as a key aspect of their experience, as shown here.

The quantitative and qualitative data highlighted an important characteristic of thirdspaces: these public gathering places are inherently community based and sustained. In response to survey question 3, about 86% of respondents indicated that they believe every community should offer members a thirdspace as a venue to socialize, collaborate on projects, and/or make and present things. About 12% of respondents were unsure, and only one respondent pushed against the idea that communities should provide these public places, explaining, “I don’t believe it is the duty of local municipal government or any other entity to offer such a place. That’s a top-down approach, which automatically makes the space uncool and unnatural. Third Spaces are and should be organic.” Other survey and design charrette participants echoed this preference for homegrown, community-driven gathering places (Hoggart & Kofman, 2015).

Reconciling Belonging and Ownership

The qualitative method of the design charrette revealed a strong tie between the sense of belonging that characterizes thirdspaces (as indicated by about 77% of survey respondents) and the sense of ownership people feel for the public places that matter to them. According to a survey respondent and two design charrette participants, an ideal thirdspace resembles or is somehow connected to a public library, where the space and resources are free and accessible to all. This thread between belonging and ownership also complicates how people define public places on the one hand and perceive their value on the other. Defining public places in relation to thirdspaces gets rather tricky because of the hybrid roles (inside or out, institutional or commercial, physical or digital) thirdspaces play (Soja, 2000).

Expanding Access

When asked whether an ideal thirdspace is primarily physical or digital, about 83% of survey respondents chose physical while the other 17% were unsure (perhaps because they needed thirdspace examples in different settings to give a definitive answer). The overwhelming preference for physical thirdspaces may correlate with the demographic makeup of survey respondents generally and with their ages specifically. As shown in the table above, nearly 41% of respondents are 65 years old or older. Central to the critical geography theoretical framework and to Marxist theory within that framework is the notion that the use of any place, whether a bricks-and-mortar location or a virtual destination, is defined by who can and cannot access it (Harvey, 1999; Lefebvre, 2000).

The use of any place, whether a bricks-and-mortar location or a virtual destination, is defined by who can and cannot access it.

Issues of access and inclusion are inextricably tied not only to the unique physical and psychological needs of community members but also to the socioeconomic disparities among them. As shown in the table above, Traverse City has a poverty rate of nearly 12% of the population, and these U.S. Census data were reported in 2019, prior to the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic (Parker et al., 2020). Coupled with the fact that, as a resort destination, Traverse City is characterized by relatively low wages and high living costs (Milligan, 2019), these data reveal that any thirdspace in the region must, for starters, “be free or very, very low priced, like public transportation,” as one design charrette participant put it. Similarly, a survey respondent expressed interest in a “no cost or very low cost space.” Although cost is not the only factor related to access (walkability is another), it is a key consideration for community members who want to create thirdspaces that everyone can enjoy.

Fostering Community Partnerships

One way to expand access on multiple levels involves building community partnerships that prioritize thirdspaces. New and possibly more experimental thirdspace initiatives, like pop-up places, benefit from networking with existing and likely more traditional thirdspaces, like public libraries. This principle drives the collaborative efforts that Horizon co-owners are making toward transforming the Horizon location into a different, more sustainable thirdspace.

Balancing Diverse Preferences and Needs

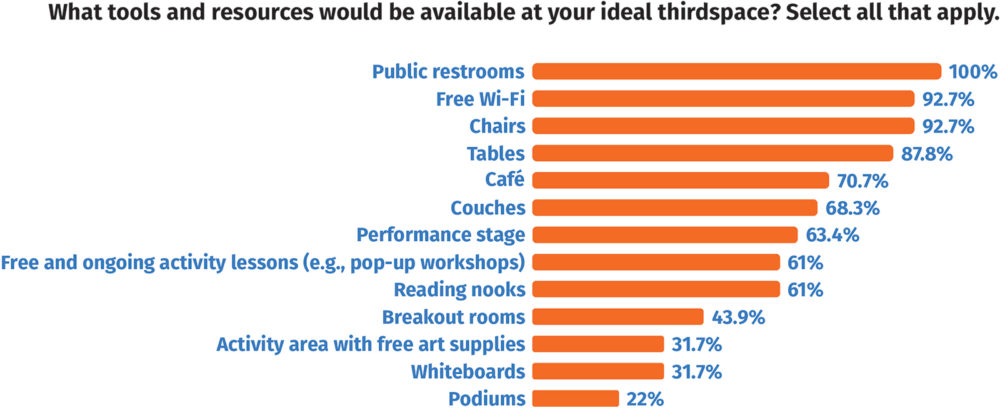

Survey questions 11–13 asked participants to imagine their ideal thirdspace and describe its characteristics. These questions built on the experience with various thirdspaces that participants brought to the survey (see above for a partial list of thirdspaces participants frequented in the past). In response to question 12, participants itemized the thirdspace tools and resources they prefer and need, as shown here.

Bringing the Outside In

The quantitative and qualitative data revealed the significance of thirdspace settings. In fact, setting is an essential concern in a region like Traverse City, which is defined by the surrounding lakeshore and natural environment. This was an especially illuminating research finding: Natural features should be integrated into thirdspaces according to five survey respondents, a request that was echoed in four sketches from the design charrette activity. If they are not already outdoor destinations, such as pop-up structures in the Traverse City State Park alongside Grand Traverse Bay, thirdspaces need to incorporate nature into their built environments. Creative approaches abound to integrating freshwater and native plant species, for example, into thirdspace settings (León, 2016; Markusen & Gadwa, 2010; Webb, 2013). In these ways, thirdspaces can help make the unique natural environment of the Traverse City region more accessible, and more enjoyable, to more community members.

Thirdspaces can help make the unique natural environment of the Traverse City region more accessible, and more enjoyable, to more community members.

Design Intervention

This project’s design outcome is a digital toolkit stakeholders may use to codesign their own physical thirdspace. The “toolkit” label situates this project within the realm of generative design research that Sanders (2008) identifies as a radical, mobilizing form of codesign. As a design research methodology that puts the power to design in the hands of a project’s stakeholders, codesign is both the guiding principle that drove the design intervention development process and the primary purpose of the intervention itself.

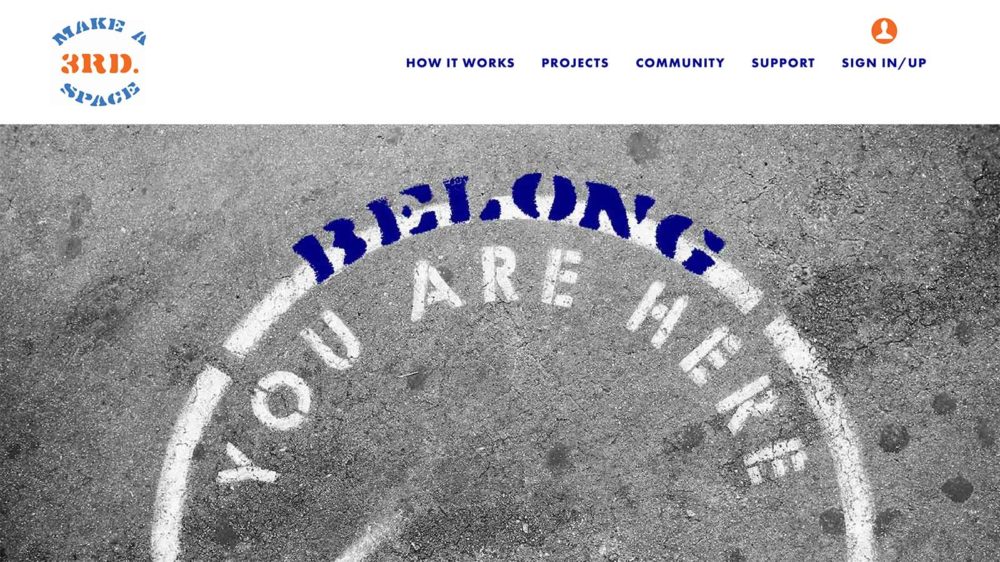

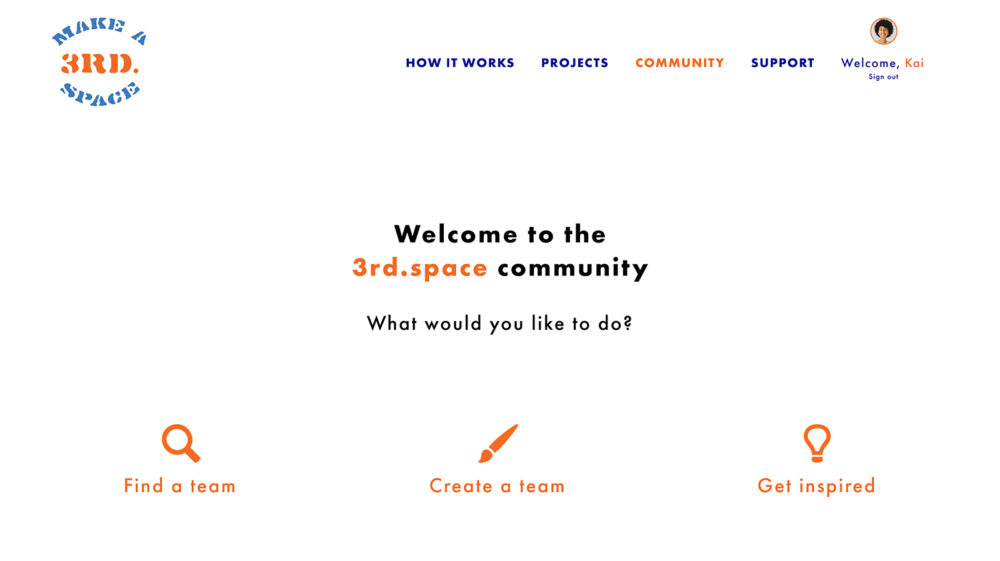

When users visit https://makea3rd.space/, they land on the homepage shown here. The top-navigation menu identifies the site’s pillar pages: How It Works, Projects, Community, and Support.

Users may visit the How It Works page without creating an account or signing in. The How It Works page features a mocked-up explainer video, viewable on YouTube.

Similar to the How It Works page, the site’s Support page does not require users to create an account to access. This page extends the informational function of the How It Works page and gives potential users the opportunity to learn more about the site and ask questions before deciding to create an account. The Support page includes a working list of frequently asked questions and a form to message the site administrator. This page also offers ongoing support for users who experience difficulties on the site or have product development ideas they want to share.

Accessing the Community page and the Projects page requires signing up for an account. Once signed in, users may select from options on the Community page to find an existing team, create a new team, and get inspired by browsing case studies of published projects. Because the Make a Thirdspace toolkit is a collaborative site, the Community page was designed to quickly connect team members to one another and their group projects.

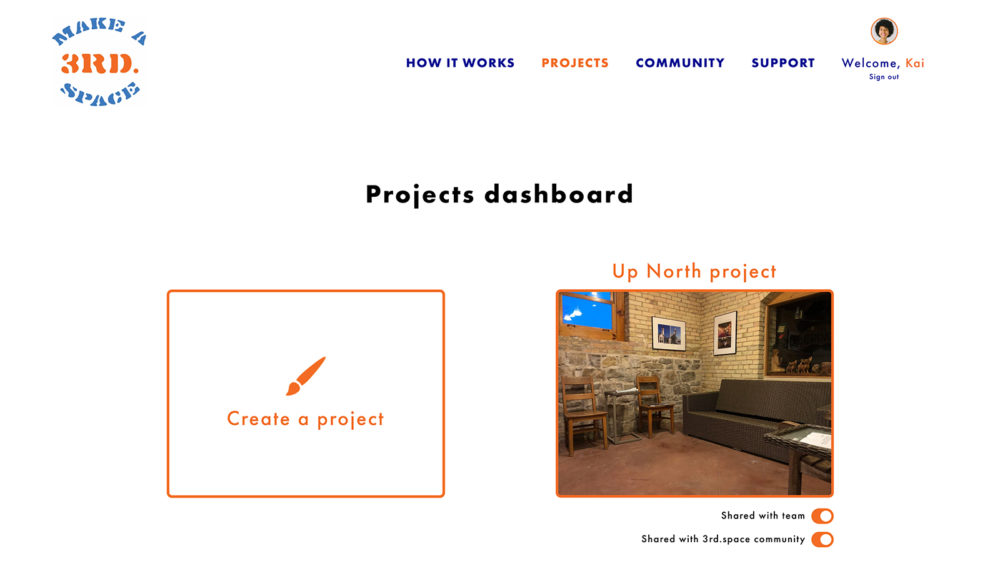

On the Projects page, users may select from options to create a new project and edit existing projects. The prototype includes a sample project called the Up North project. Sharing settings per project are also accessible from this page.

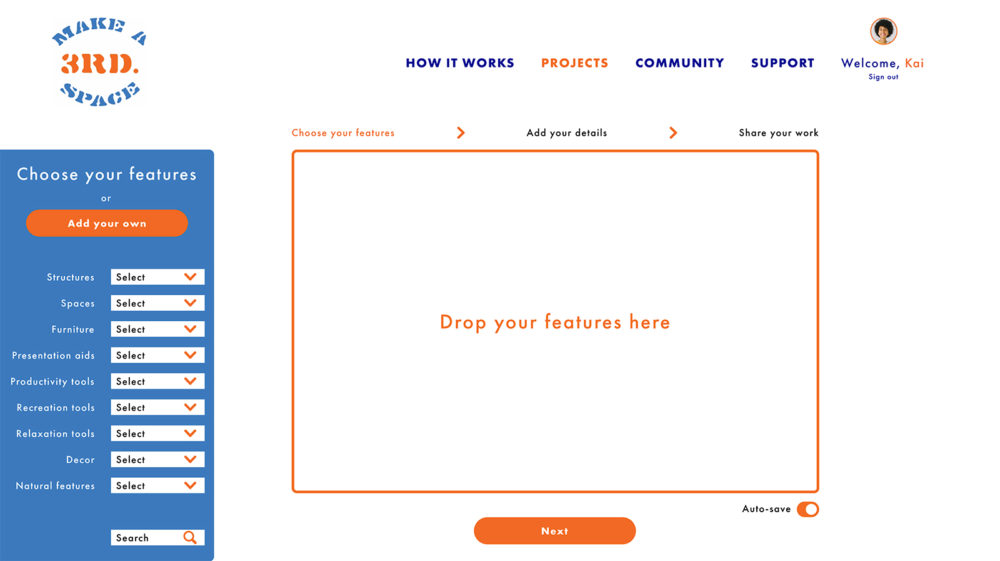

The prototype guides users through the various steps involved in planning and building a thirdspace in a digital setting. Once users select a shape and size for their place, they may then design the features of the place. The Choose Your Features page includes options to drag and drop pre-loaded features onto the blank canvas and to sketch and add custom features to the library.

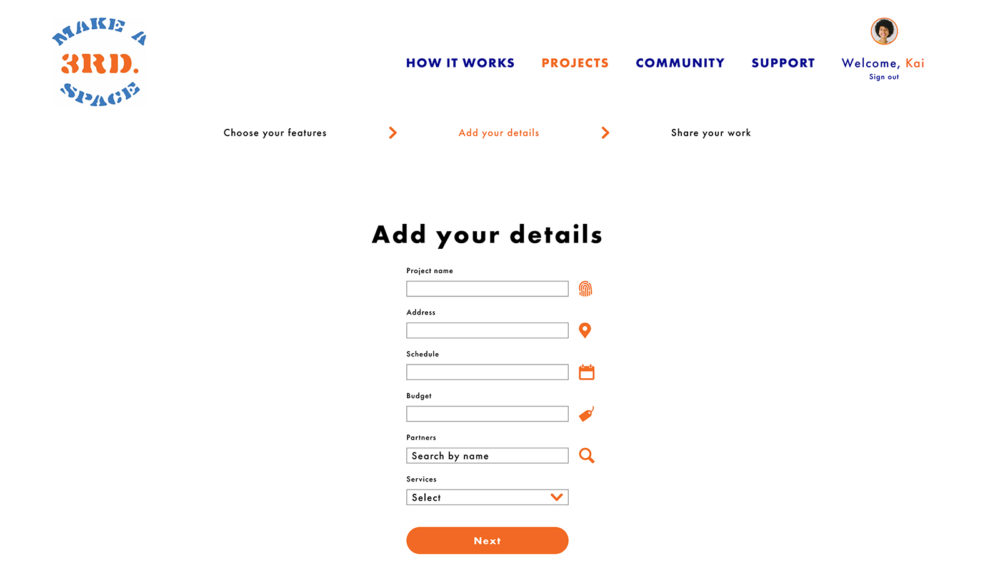

After features are chosen for a project, project details may be added to easily identify and return to a project in progress. The Add Your Details page includes options to flesh out project details such as name, location, schedule, budget, partnerships, and services.

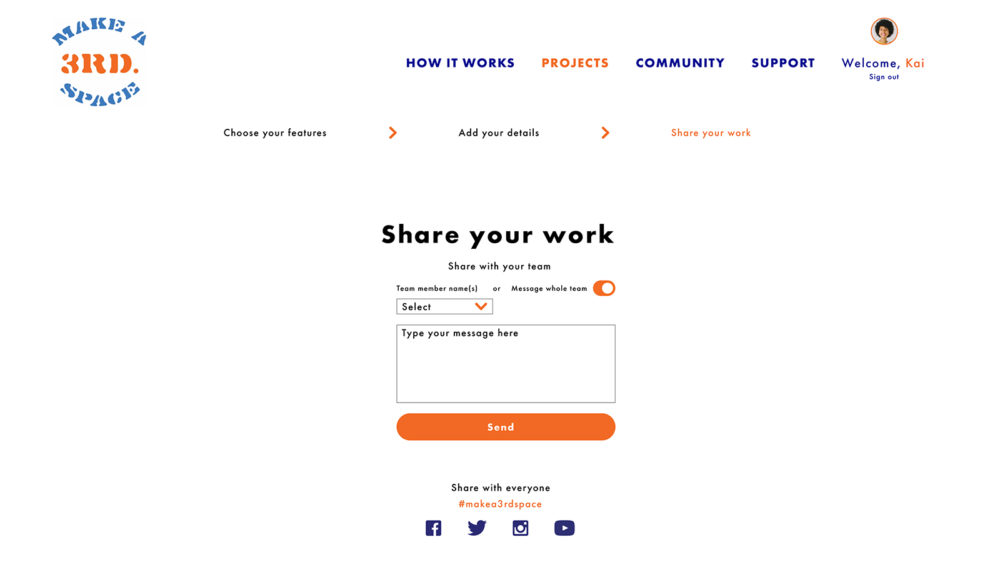

Finally, users are encouraged to share their work with team members and, if they prefer, with the Make a Thirdspace community. From the Share Your Work page, users may notify team members of project updates and share project developments on social media with the #makea3rdspace hashtag.

Prototype Testing

To evaluate the effectiveness of the design intervention, a usability test was conducted with three of the six design charrette participants. It was one of the four data collection methods selected for this project, as described above. The test generated practical data about usability limitations of the design prototype as well as qualitative data about participant needs and expectations. These data were then triangulated, analyzed, and coded to discover overarching themes and patterns in a process resembling the project’s overall research design.

The usability test took place on Zoom in three individual sessions as participants each completed seven tasks (using a supplied design review link to the prototype in Adobe XD) and answered some introductory and follow-up questions. Unlike my participant-observer role in the design charrette, my role in the usability test was far less participatory and instead shaped by the goal of learning about each participant’s unique experience with the prototype. To this end, I provided initial instructions to testers, moderated and took notes during the sessions, and answered questions that arose (although I intentionally let participants try to figure out any issues they encountered rather than guiding them through the prototype). Testers were encouraged to use a think-aloud process that revealed key functionality limitations and insights.

Testers were encouraged to use a think-aloud process that revealed key functionality limitations and insights.

The usability test generated insights in six major categories:

- Design: Testers described the overall site design as “clean,” “simple,” and “open,” making the experience of conceptualizing a thirdspace “fun” and inviting. One tester acknowledged the prototype’s personalized look and feel, although personalization was enhanced in a revised version of the site. Two testers mentioned liking the color scheme, and one thought it appropriately conveyed a building space or construction vibe. One tester liked how the site design puts the canvas at the center of the user experience. Generally, testers found the site navigation fairly intuitive, although each tester spotted the same navigation glitch in the sequence of building a thirdspace that was subsequently fixed. Suggestions for future design improvements include a hover-and-expand top-navigation menu and quicker navigational access to teams and projects in progress.

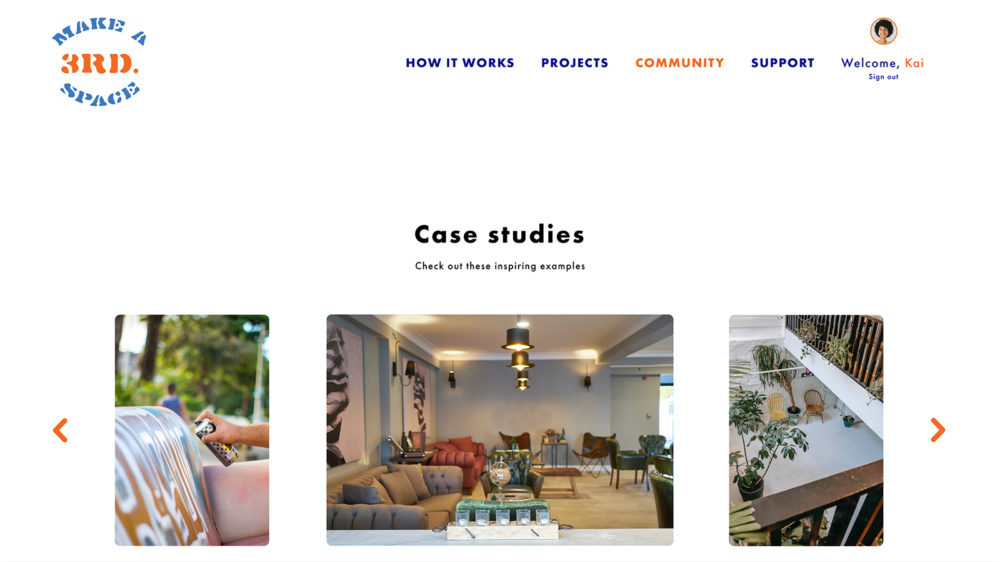

- Context: Each tester wanted more contextual information to explain the intended audience and purpose of the site and the relevance of the thirdspace concept to target users. It became clear early in the testing phase that an explainer video would go a long way in setting the stage for the design intervention and the need it fills. After the site was revised to incorporate tester feedback, this video was created and posted to YouTube. Similarly, one tester wanted to know more about the site’s author or sponsor. This tester also asked for more contextual examples of different applications of the toolkit in various communities. These examples could be added to the Case Studies page shown below.

- Features: The Choose Your Features page was built to serve as the heart of the toolkit. It was strategically developed to “contain a collection of ambiguous (as well as unambiguous) elements” in order “to trigger associations in the area of [user] experience that is studied” (Sanders & Stappers, 2013, p. 57). In other words, the usability test was incorporated into this project as a data collection method to gather ideas from testers about what specific tools they want to see on the site. To this end, categories of tools (such as furniture and productivity tools) were listed on the Choose Your Features page of the prototype, but the canvas was intentionally left blank to literally give testers the space to imagine their own ideal toolkit. In this way, the usability test was, like the design charrette, a cocreative activity that generated valuable insights about the possibilities for such generative toolkits.

- Collaboration: All three testers liked the prototype’s focus on collaboration. When asked to describe the prototype in their own words, two testers specifically mentioned the collaborative nature of the toolkit, although one tester asked for a quicker and easier set of tools to communicate with teams. While completing certain tasks on the site, the third tester mentioned liking the options on the Community page, complimenting the Find a Team option in particular. Based on testing feedback, the Search by Member Name option was moved to the top of the list of search mechanisms. One tester especially liked the geographical emphasis in the Search by Location option.

- Privacy: Two testers raised potential privacy concerns with the toolkit. Specifically, one tester needed more contextual information about the site to feel comfortable signing up for an account. This comment, among others, drove the creation of an explainer video as described above. At the same time, this tester wanted the site to use cookies to remember user sessions and “drop” users directly into relevant team projects. Another tester wanted to know how to set sharing permissions for individual projects, prompting the addition of the sharing toggle switches to the Projects page.

- Resources: Only one tester called out the newsletter subscribe button at the bottom of each page of the prototype. This tester was intrigued by the newsletter and wanted more information about its content and frequency.

Conclusions

The prototype that was developed for this project’s design intervention is just one solution in progress for the various stakeholder needs served by generative toolkits. In its current state, the Make a Thirdspace toolkit is actually more of a shell—or an empty “toolbox” to again borrow language from Sanders and Stappers (2013)—that invites users to contribute, reflect, and revise together. The collaborative nature of the website user experience therefore mimics the site’s collaborative development process itself. This development process was heavily influenced by the usability test overall and the specific expertise three Traverse City stakeholders brought to the testing environment. This project could not possibly anticipate the vast range of places that people could create with the Make a Thirdspace toolkit. And that uncertainty is terribly exciting.

Suggestions for Future Research, Testing, and Design

This project opened the door to several research, testing, and design opportunities. The project’s success depends on continuous user feedback. As more users contribute to the toolkit, the more it will serve a range of stakeholder needs in a range of contexts. Two key areas for future design developments include the following:

- Choose Your Features page: Ideally, the Choose Your Features page developed for the prototype would provide a blueprint for developers to make the toolkit fully functional. Additionally, one tester suggested enhancing the user experience with 3D views of projects while being built. Incorporating augmented reality into the website user experience, perhaps by integrating a platform like Metaverse, would help merge the digital and physical settings where people create and use thirdspaces (Yuen & Johnson, 2017).

- Thirdspace resources: The site’s instructional and inspirational resources could be further developed to help attract more and varied users, who would bring their unique expertise to the Make a Thirdspace community. Future developments could include a blog, tutorial hub, and public group on Facebook to help users get the most out of the toolkit. With the proper permission, user projects and experiences could be compiled and featured in the Make a Thirdspace newsletter and Case Study gallery.

This project invites future investigations into the values and needs that drive communities around the country and world to reimagine themselves through equitable and revitalizing partnerships. These partnerships—between individuals, groups, organizations, and/or businesses—can open doors to more and varied opportunities for more and varied community stakeholders. Future research could involve entirely different and more diverse populations in the design process from start to finish. Incorporating the perspectives and needs of underrepresented populations in particular—including women, people of color, and the poor—is crucial at a time when such perspectives and needs are, to varying extents, being downplayed or dismissed. All stakeholders deserve to feel like they belong in their communities. And all stakeholders deserve to have a hand in how their communities develop.

All stakeholders deserve to have a hand in how their communities develop.

Being able to envision and actually build a better, more inclusive future for our communities requires, for starters, a toolkit that everyone can use. This project offers just one such toolkit that was designed from the research conducted with just one small community. The kinds of places that people build with the toolkit are endless. So too are other possible toolkit outcomes that might operate completely differently than the Make a Thirdspace toolkit. I eagerly await your ideas.

References

Allen, K.-A. (2021). The psychology of belonging. Routledge.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Crosbie, M. J. (2021, January 13). Assault on a sacred place. CommonEdge. https://commonedge.org/assault-on-a-sacred-place/

Harvey, D. (1999). Justice, nature and the geography of difference. Blackwell Publishers. (Original work published 1996)

Hoggart, K., & Kofman, E. (2015). Introduction. In K. Hoggart & E. Kofman (Eds.), Politics, geography & social stratification (pp. 1–15). Routledge. (Original work published 1986)

Lefebvre, H. (2000). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Blackwell Publishers. (Original work published 1991)

León, M. L. D. (2016, November). Ethics of development: A shared sense of place. In How to do creative placemaking: An action-oriented guide to arts in community development (pp. 78–81). National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/How-to-do-Creative-Placemaking_Jan2017.pdf

Lewis, T., Amini, F., & Lannon, R. (2000). A general theory of love. Random House.

Link, M. (2020, January 19). Following announcement of closure, outpouring of support for Horizon Books. Traverse City Record-Eagle. https://www.record-eagle.com/news/local_news/following-announcement-of-closure-outpouring-of-support-for-horizon-books/article_fdfac608-3972-11ea-bf3a-632faa1fec01.html

Markusen, A., & Gadwa, A. (2010). Creative placemaking. National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/CreativePlacemaking-Paper.pdf

Milligan, B. (2019, August 11). Economic study shows region has higher living costs, lower incomes, declining young population. The Ticker. https://www.traverseticker.com/news/economic-study-shows-region-has-higher-living-costs-lower-incomes-declining-young-population/

Norman, D., & Spencer, E. (2019, January 3). Community-based, human-centered design. JND. https://jnd.org/community-based-human-centered-design/

Parker, K., Minkin, R., & Bennett, J. (2020, September 24). Economic fallout from COVID-19 continues to hit lower-income Americans the hardest. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/09/24/economic-fallout-from-covid-19-continues-to-hit-lower-income-americans-the-hardest/

Sanders, L. (2008). An evolving map of design practice and design research. ACM Interactions, 15(6), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1145/1409040.1409043

Sanders, L., & Stappers, P. J. (2013). Convivial toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design. BIS Publishers.

Soja, E. W. (2000). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Blackwell Publishers. (Original work published 1996)

Top 10 charming small towns. (2010, June 19). Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. http://archive.jsonline.com/features/travel/96676699.html

VanderMeulen, J. (2011). Placemaking and resilient communities. In C. Layton, T. Pruitt, & K. Cekola (Eds.), The economics of place: The value of building communities around people (pp. 109–128). Michigan Municipal League.

Vey, J. S. (2018). Why we need to invest in transformative placemaking. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/why-we-need-to-invest-in-transformative-placemaking/

Webb, D. (2013). Placemaking and social equity: Expanding the framework of creative placemaking. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 3(1), 35–48.

Yuen, F., & Johnson, A. J. (2017). Leisure spaces, community, and third places. Leisure Sciences, 39(3), 295–303.

OhioLINK Access

xdMFA Candidates must disseminate their research online in the Ohio Library and Information Network (OhioLINK) Electronic Theses and Dissertations repository. This thesis may be accessed at http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=miami1588331262095651