Designing a Strategy to Reduce Wedding Conflict for Engaged Christian Couples with Progressive Values

This study was designed to discover what strategies Christian couples with progressive values who are engaged to be married can use to plan a wedding that honors their beliefs and prepares them to be partners in a marriage that values egalitarian principles. Attitude changes in the last decade support progressive values and social reform in regards to wedding celebrations, however Christian couples who have progressive values continue to launch their marriage with a traditional wedding full of sexist traditions and gender normative implications. 22 survey participants, three of which were interviewed, were studied to learn their views on Feminism and wedding traditions. A website intervention was designed based on these responses that used marriage coaching during the wedding planning process by simulating wedding and marriage tasks. Through these solutions, the intervention was designed to help these couples establish a more egalitarian relationship, navigate relationship conflict, recognize sexist traditions while honoring and respecting their religious affiliation, and establish autonomy from family. The outcome of this design was tested on new participants, and this study reports results which revealed that participants required more incentive to interact with a marriage coaching service, and they valued counselors who had professional credentials or certifications.

Introduction

Background

Marriage began as a way to secure property rights. The wife came with a dowry in the state that would be passed down for generations, and it really wasn’t until the 18th century when people started actually marrying for love (Coontz, 2006; Gendler, 2014; Zeff, 2002). But even now, women still face the expectations of being a homemaker and childbearer, and they are even expected to look forward to their roles (Butler, 1990; Friedan, 1963; Gendler, 2014; Martos, 1998; Tong, 2001; Tyson, 2006 & Zeff, 2002).

Women are also taught to fantasize about weddings growing up and men are taught generally to be uninterested (Engstrom, 2008; Humble et al, 2008; Sniezek, 2005). Weddings are associated with the aesthetic quality of femininity, and men are taught to believe that anything that’s associated with feminine qualities is considered weak or less-than (Engstrom, 2008 & Sniezek, 2005. The Christian Bible reinforces this attitude also by asking women to “obey” or “submit” to their husbands as slaves do to their masters (1 Corinthians 11:3, NRSV), and many biblical references position men over women (Ruether, 2014 & Ruether, 1993). These gender roles continue to be seen even in a more progressive modern era (Erickson, 2013; Maltby et al., 2010; Ruether, 2014 & Ruether, 1993).

The Western world has seen an increase in tolerance for cohabitation, interethnic, interfaith and same sex marriages in the last 10 years (Fairchild, 2013; Parker et al, 2019; Pew Research Center, 2014; Kalmijn, 2014; Livingston & Brown, 2017; Murphy, 2015; Stepler, 2017 & Support for Same-Sex Marriage, 2017), leading to an increase in liberal progressive values in the general public, including Christians (Erickson, 2013 & Ruethe, 1993). Many of these Christians actually reinterpret sexist teachings to coexist with their more modern personal values (Ruether, 1993). For example, there are plenty of Christian women who don’t actually believe that they are slaves to their husbands. Despite these acommodations, engaged Christians do still face conflict, especially in heteronormative relationships that consist of an man and woman (Erickson, 2013; Maltby et al., 2010; Ruether, 2014 & Ruether, 1993).

Conflict in relationships is totally normal and inevitable (Canary et al., 1995; Knee et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2008). Instead of preventing conflict, couples can establish relationship satisfaction and intimacy by learning how to handle conflict through constructive conflict behaviors (Canary et al., 1995. Constructive conflict behaviors allow relationships to grow and give partners a chance to express individuality and establish equality in the relationship (Knee et al., 2005 & Simon et al., 2008).

Problem Statement

So what’s the problem? Engage Christian couples with progressive values are still having traditional weddings that support sexist attitudes even if they subscribe to progressive lifestyles. For example, a lot of people cohabitate nowadays and support equality in heteronormative relationships (Fairchild, 2013 & Stepler, 2017). Then the first thing that they do as a married couple is have this hyper traditional wedding that’s littered with sexist implications and gender roles that are associated with marriage. This causes tension between couples when they feel pressure to adhere to gendered displays that go against their personal values (Butler, 1990; Friedan, 1963; Martos, 1998; Tong, 2001 & Tyson, 2006).

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study is to promote personal well-being and satisfaction in relationships by designing an intervention that reduces the problem of conflicting personal and religious values and tension between engaged couples during the wedding planning process.

Research Question

What strategies can Christian couples with progressive values who are engaged to be married, use to plan a wedding that honors their beliefs and prepares them to be partners in a marriage that values egalitarian principles?

Phenomena Research Findings

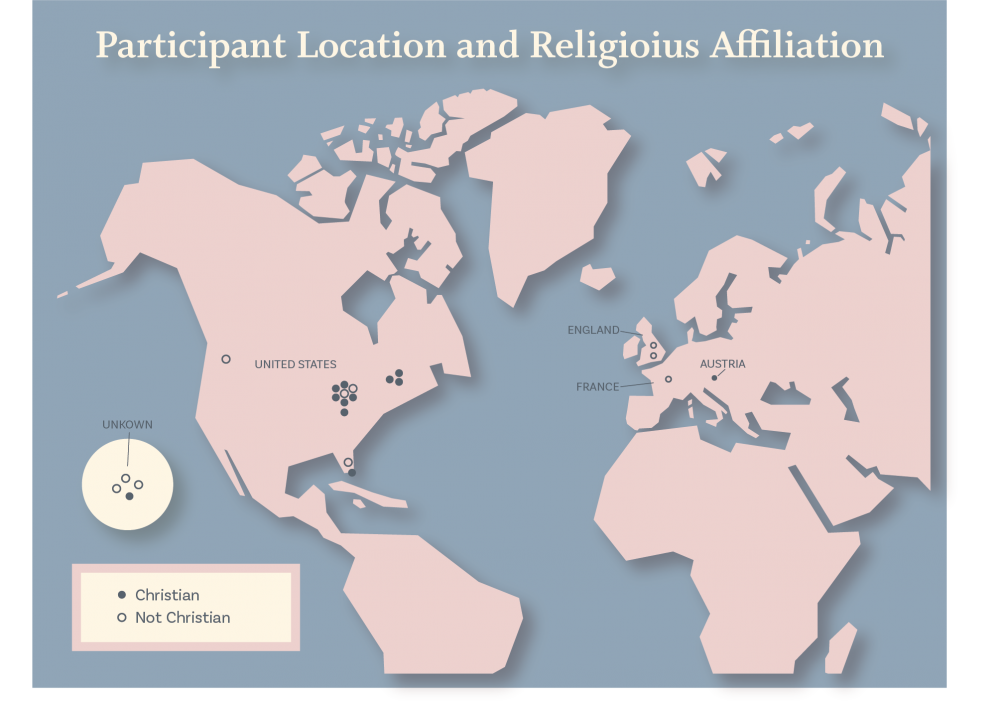

I conducted a survey of 22 participants in Western Europe and North America, three of which were then interviewed in more depth. 54.5% of these participants identified as Christian.

Perceptions of Feminism

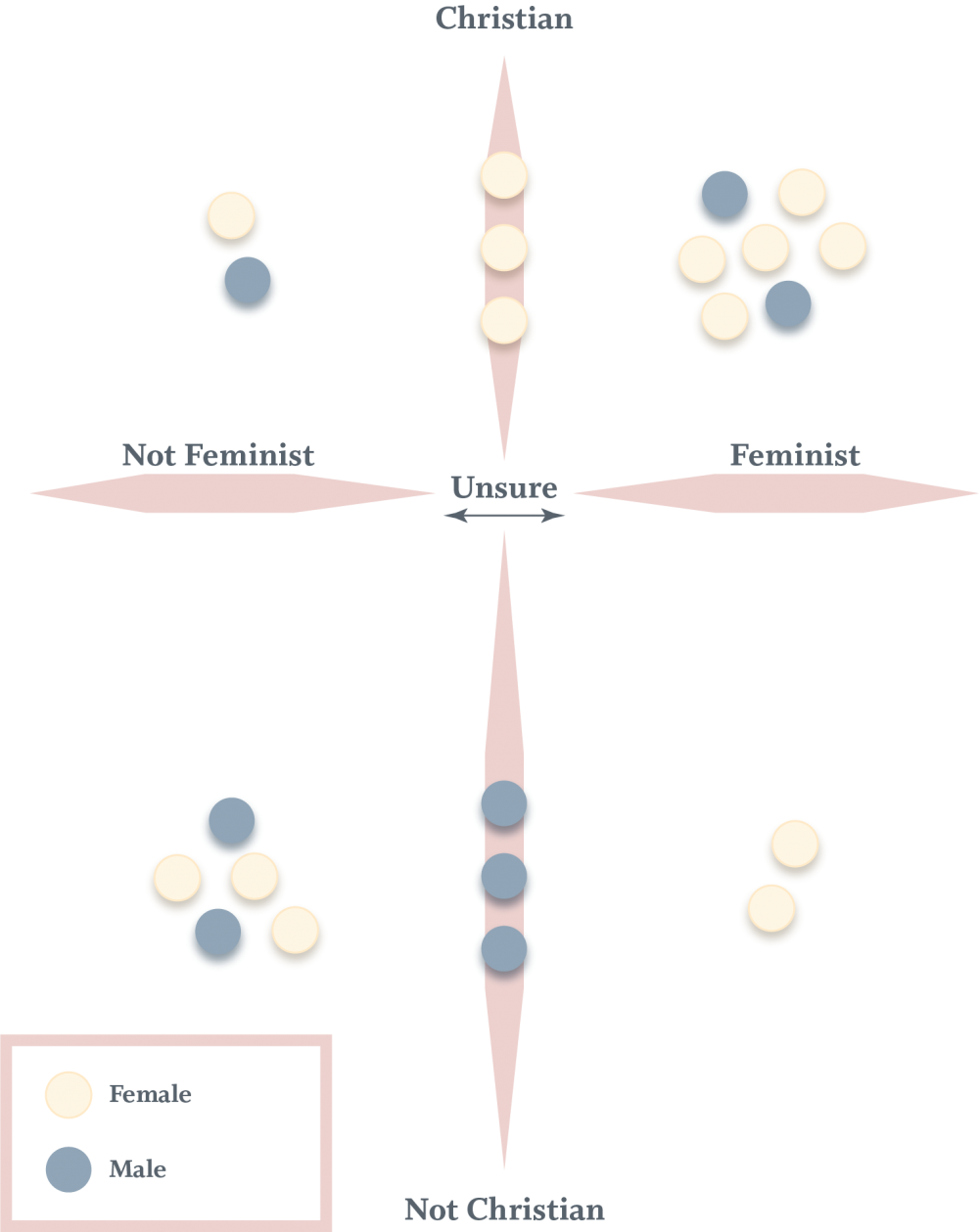

75% of the Christians were females, so a lot of my results are based on the perceptions and opinions of females. Almost 78 percent of the Feminist participants identified as Christian, which was actually an unexpected finding. I expected that they wouldn’t want to identify as Christian because initial research indicated that Christian’s typically don’t politically align with the modern polarizing term of “Feminism” (Maltby et al., 2010).

Perceptions of Gender Norms

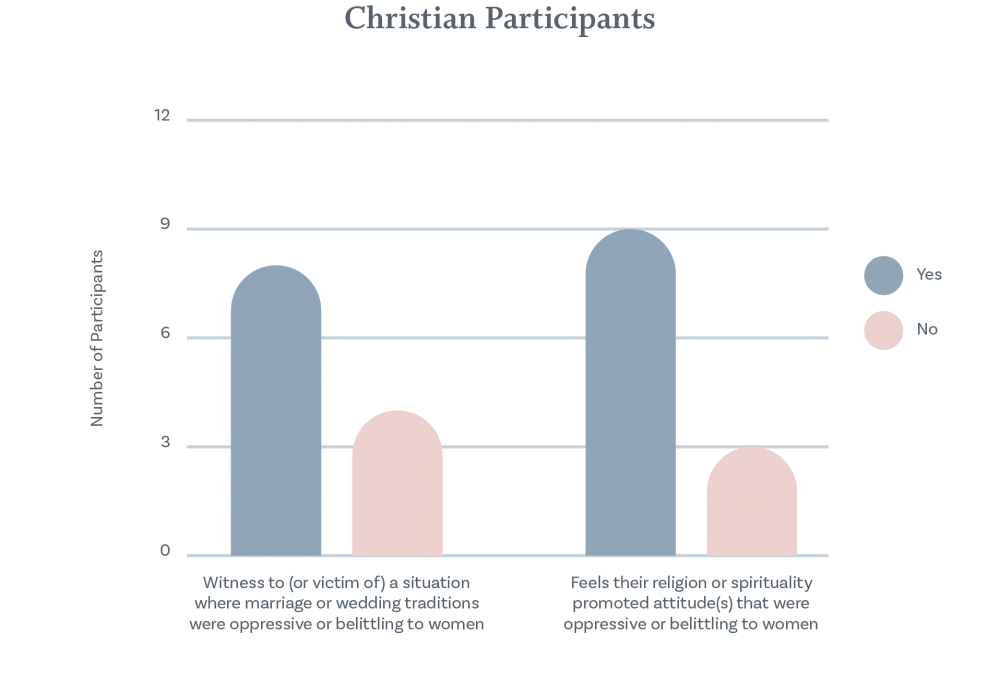

It was pretty clear to me that Christians saw more oppression than the Non-Christian participants, which is another unexpected finding. They especially felt that their religion promoted attitudes that were repressive or belittling, which shows that they have an extreme awareness of the oppressive nature of their own religion.

Personal Values and Social Pressure

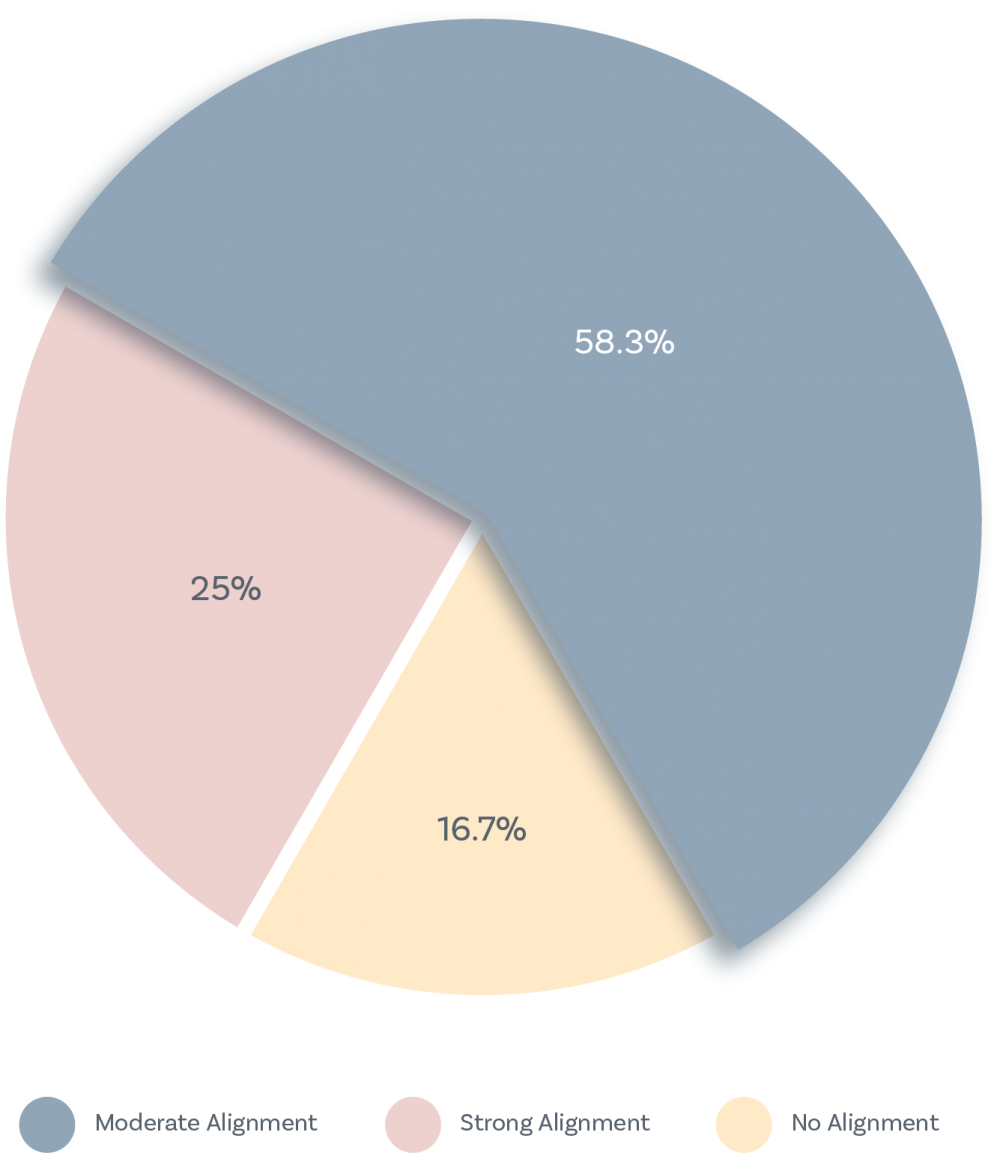

Most of the Christian participants had moderate alignment with their religious affiliation. Two of the interview participants, however, strongly aligned with their faith, and they said that it was because it was important for their family.

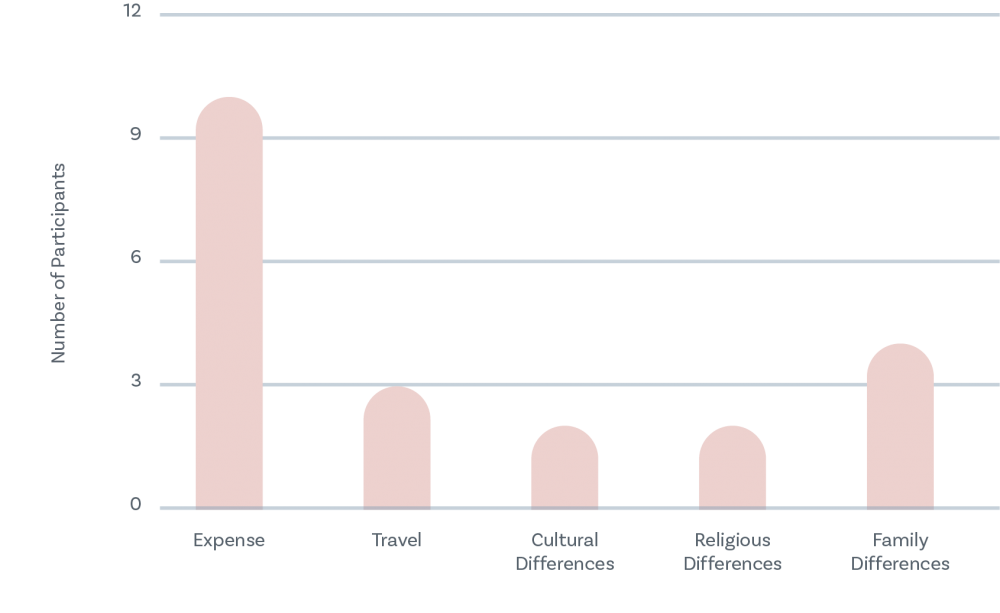

There was a lot of family influence on motivation for the participants. While that’s normally a positive thing to have a social bond with family, it led to participants experiencing pressure from their family that made them feel forced to make decisions in the wedding planning process.

Financing the Wedding

Expense was a leading wedding concern for participants. In most cases, the participants’ parents paid significantly for the wedding thing. This led to more pressure to make parents happy. One participant who was a divorce lawyer said that the same money power struggle is the leading cause of divorce in marriages.

Oppressive Traditions

Participants said they didn’t like wedding traditions such as the garter toss, the “obey” vows, and the father giving the bride away. Participants also said they didn’t like marriage traditions such as the wife’s responsibility of sexually pleasing her husband, bearing children, and taking the husband’s name. Some claimed to reframe Christian traditions to fit their more progressive views.

Distribution of Labor and Gender Norms

75% of the participants said that both partners should plan the wedding together. One participant regretted having to plan the wedding herself and said she really wished that she’d gone back and asked her husband to be more involved. In a lot of cases, women gathered information and made decisions on their own. Then they would present the refined options to their husband in order to involve them in some small way.

Navigating Conflict Between Partners

Participants mentioned how unrealistic expectations caused them to be disappointed with the reality of marriage and the conflict that surfaces. One participant said she didn’t have a glamorous honeymoon because she didn’t want to come back and be disappointed.

Some participants regretted prioritizing the opinions of their family over their significant other, and if they could go back, they would have put more weight on their fiancé’s opinion.

Another participant said that she thought that pre-marriage counseling would have been valuable to her. She had actually done some marriage counseling with her officiants (she had two), and she really liked that “humble perspective” that she got from the experience. If she could go back, she said she would have done more pre-marriage counseling, but the negative stigma of professional counseling kept her from taking that leap.

Design Intervention

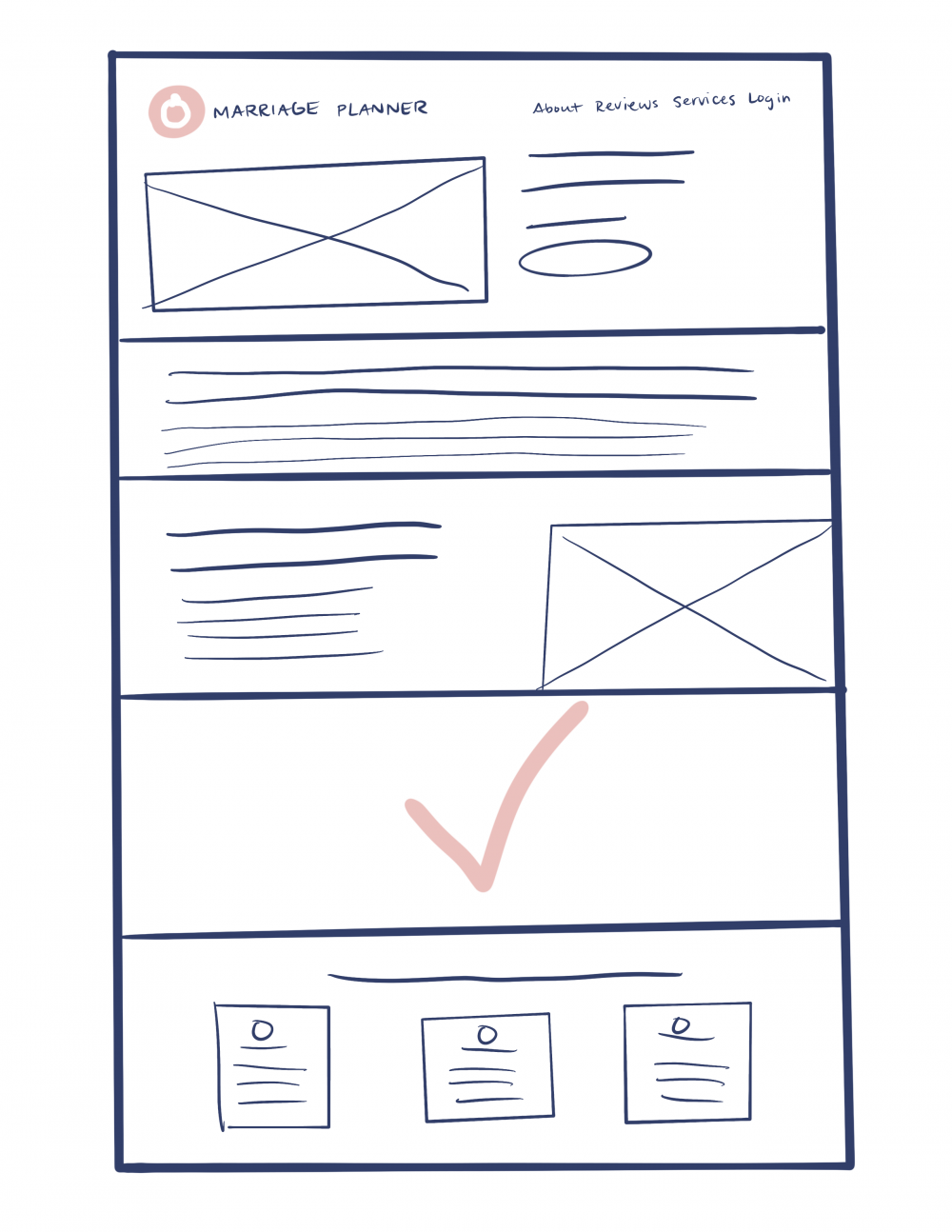

The design intervention I created in response to the findings in this study is a website called “Marriage Planner”. Marriage Planner is a website for planning weddings and also for planning marriage. It helps couples build a relationship that promotes equality between partners while also introducing pre-marriage counseling through a “marriage coach”. Click the following button to see a walkthrough of the Marriage Planner prototype.

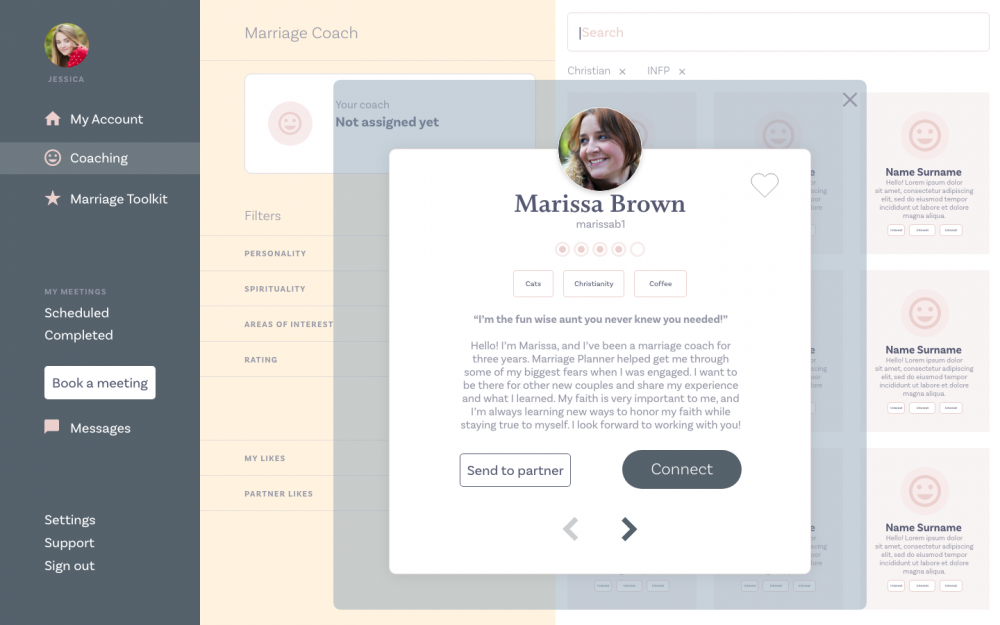

These marriage coaches are regular, everyday people, and they offer an informal and more personal alternative to professional counseling. While they’re non-professionals, they are trained to use therapy methods to assist couples in thinking critically about their attitudes. These marriage coaches are also trained in certain topics covered in this study such as feminism, ethics of counselling, personal well-being, relationship conflict, and wedding traditions.

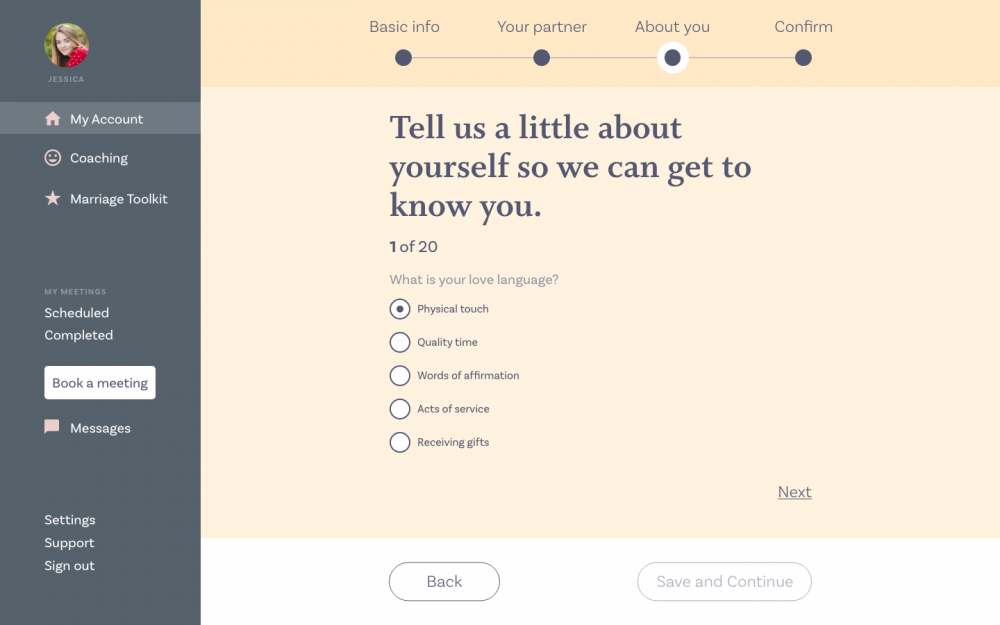

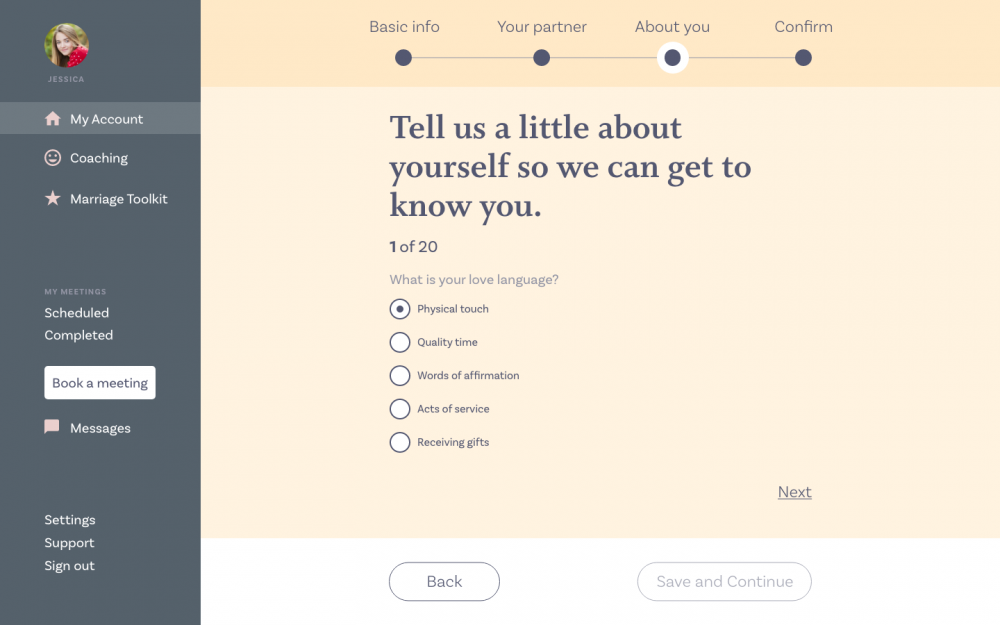

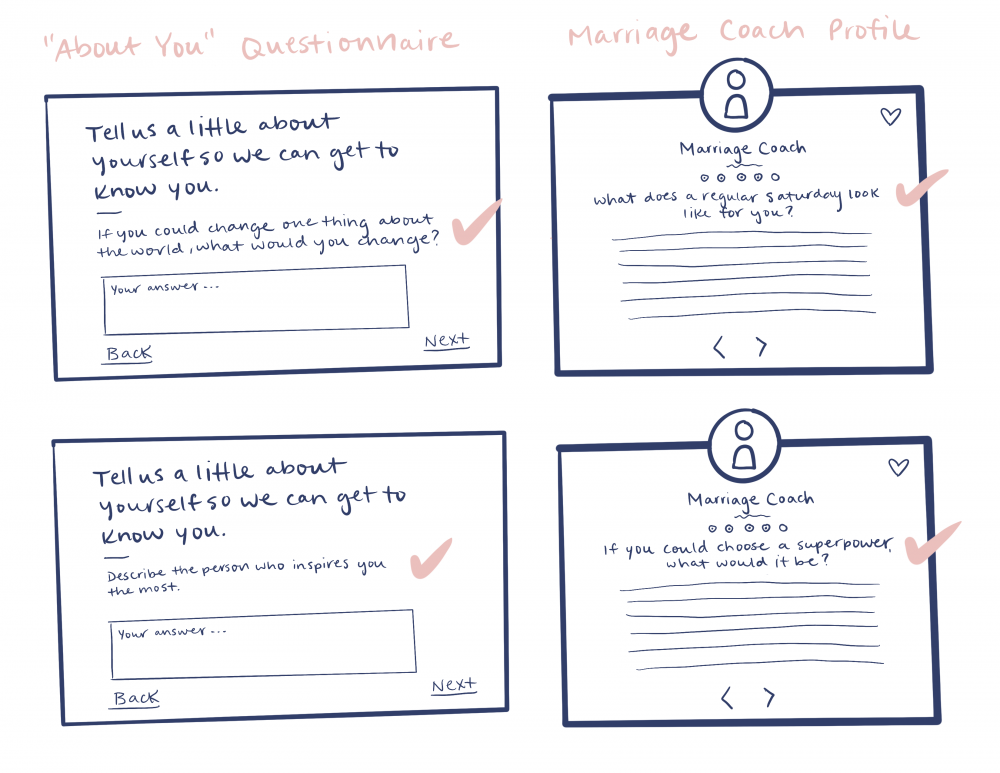

As couples enter the website, they individually complete an “About You” Questionnaire that asks questions about their personality and perceptions of relationships.

Once they complete the questionnaire, they can compare answers with one another and move on to connect with a marriage coach through the marriage coach search database.

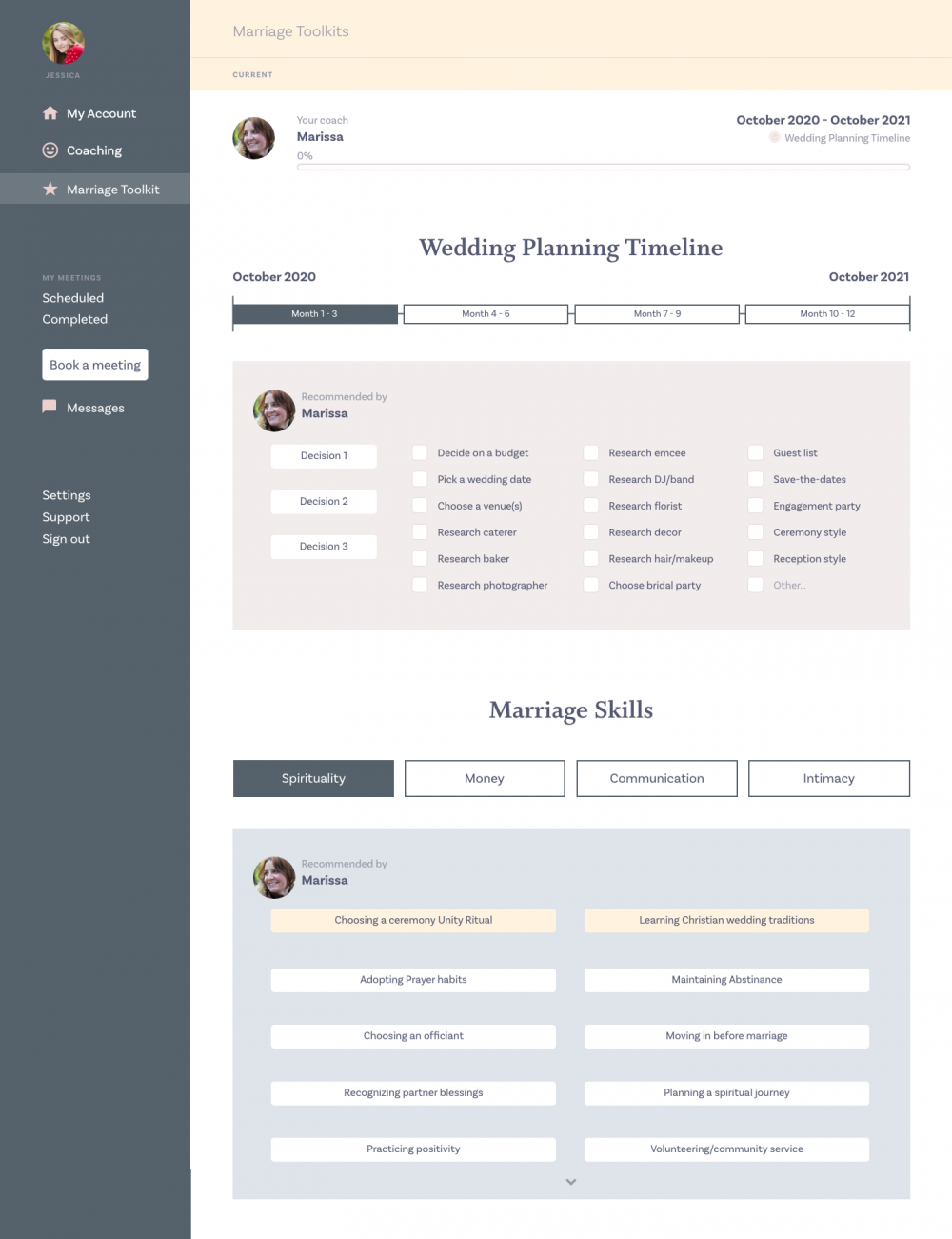

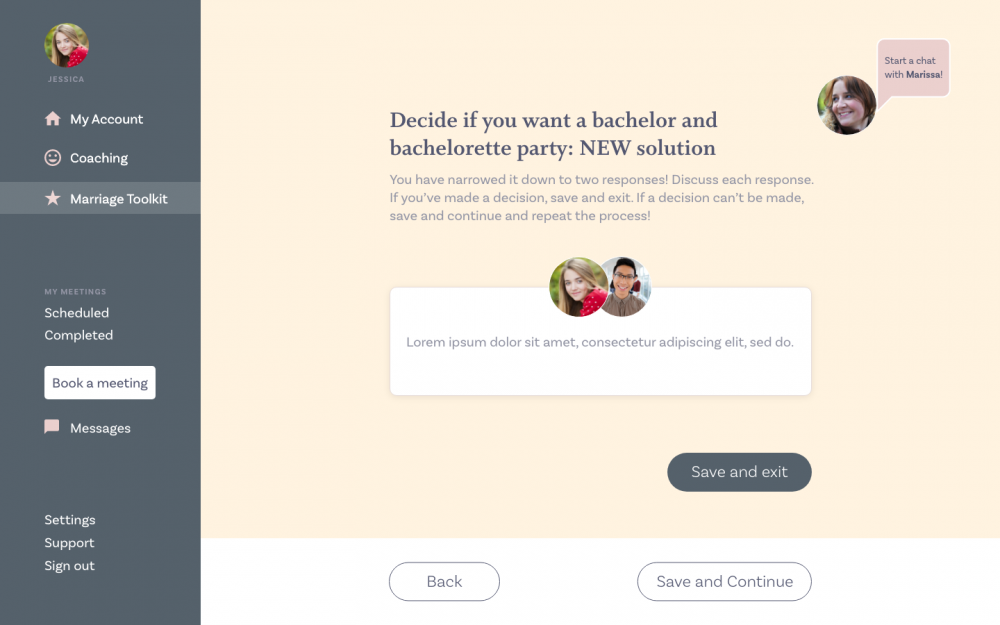

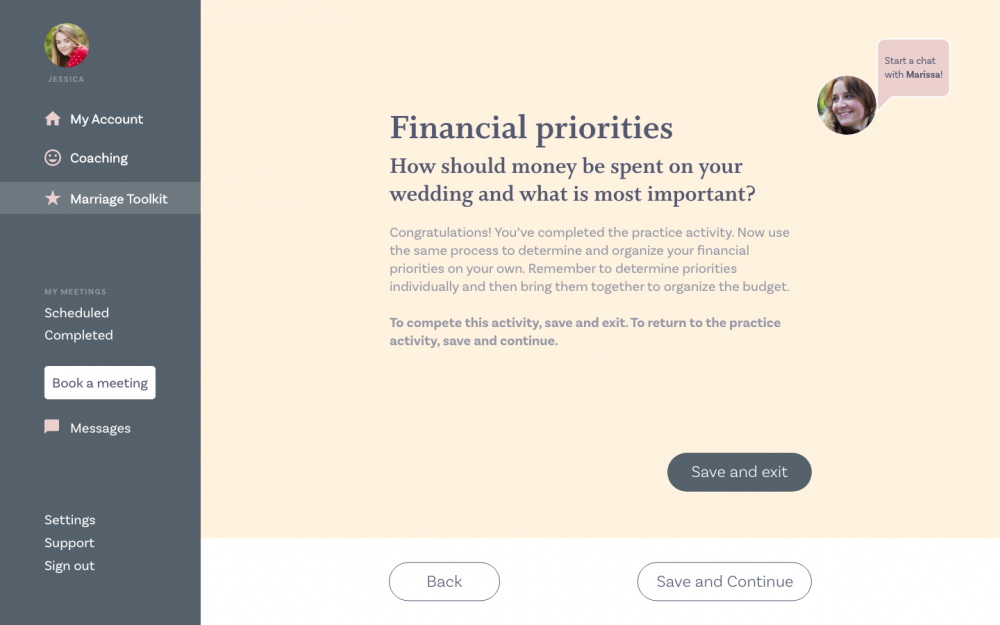

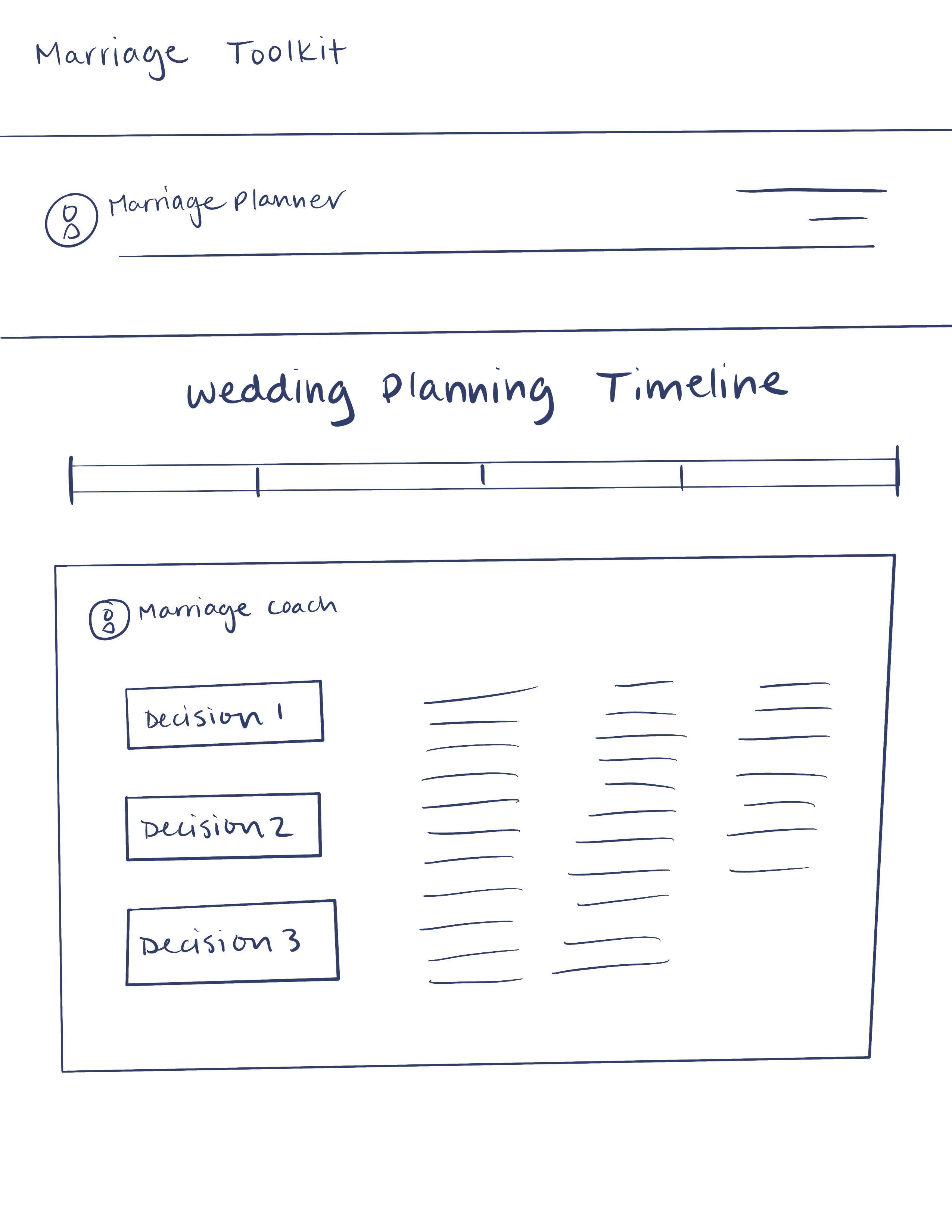

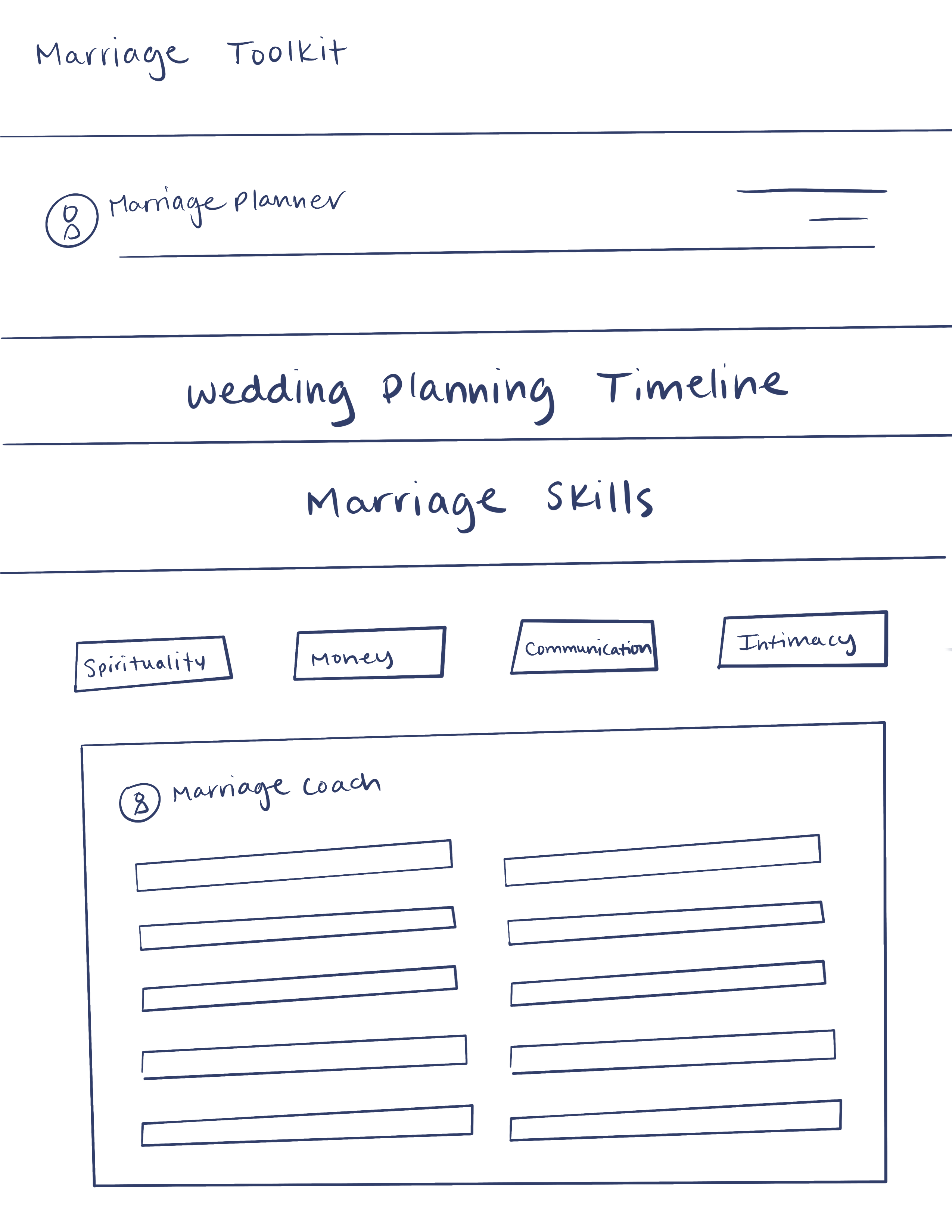

Once they pick a marriage coach together, they each meet with the marriage coach separately via video and answer questions about their needs and values in regards to both their wedding and marriage. Once each meeting has been conducted, the marriage coach customizes a “Marriage Toolkit”, complete with a “Wedding Planning Timeline” and a “Marriage Skills” section.

In each of these sections, the marriage coach recommends activities that simulate relationship-building skills that allow the couples to grow closer and establish equality.

Prototype Testing

I tested the Marriage Planner prototype on a Christian couple who was already married to see how effective the website was.

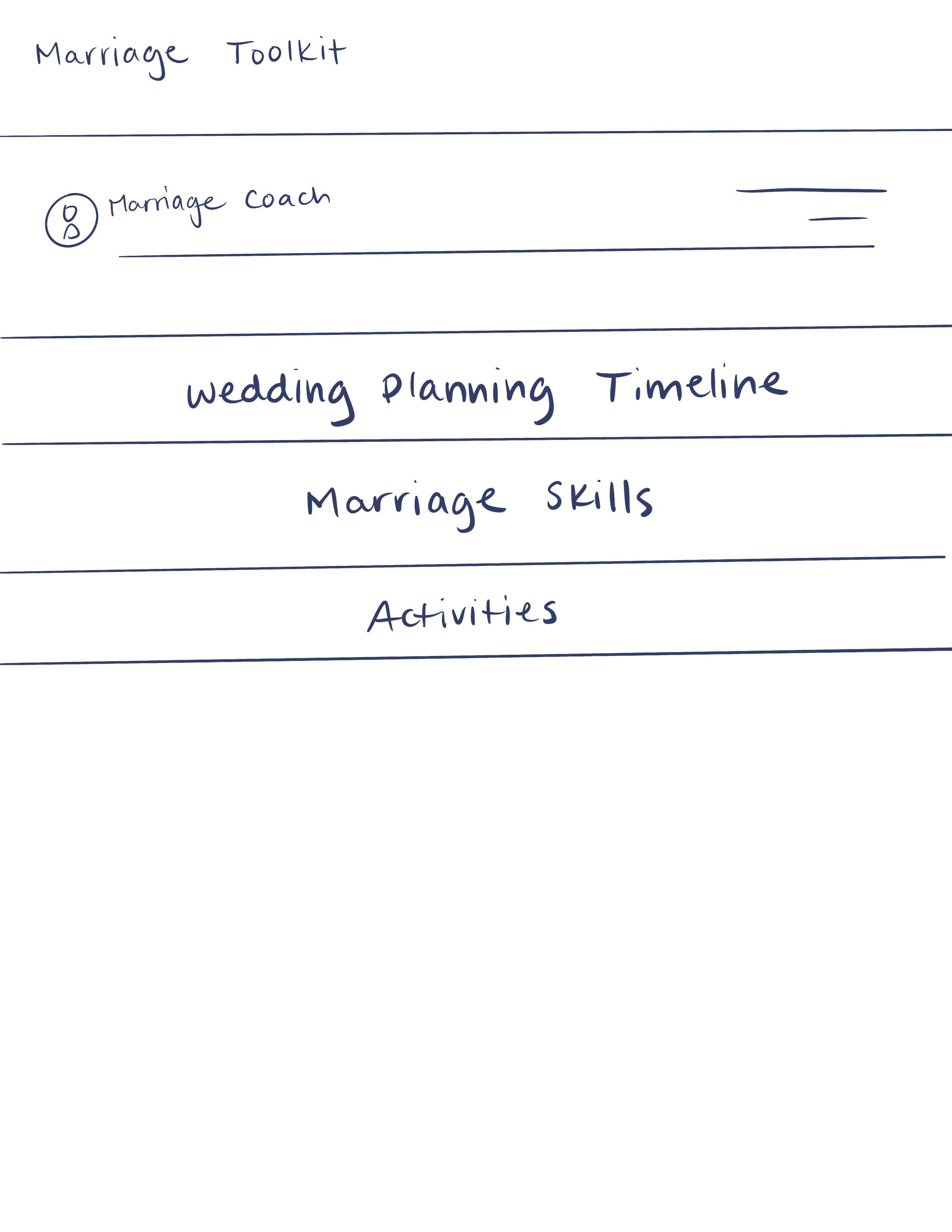

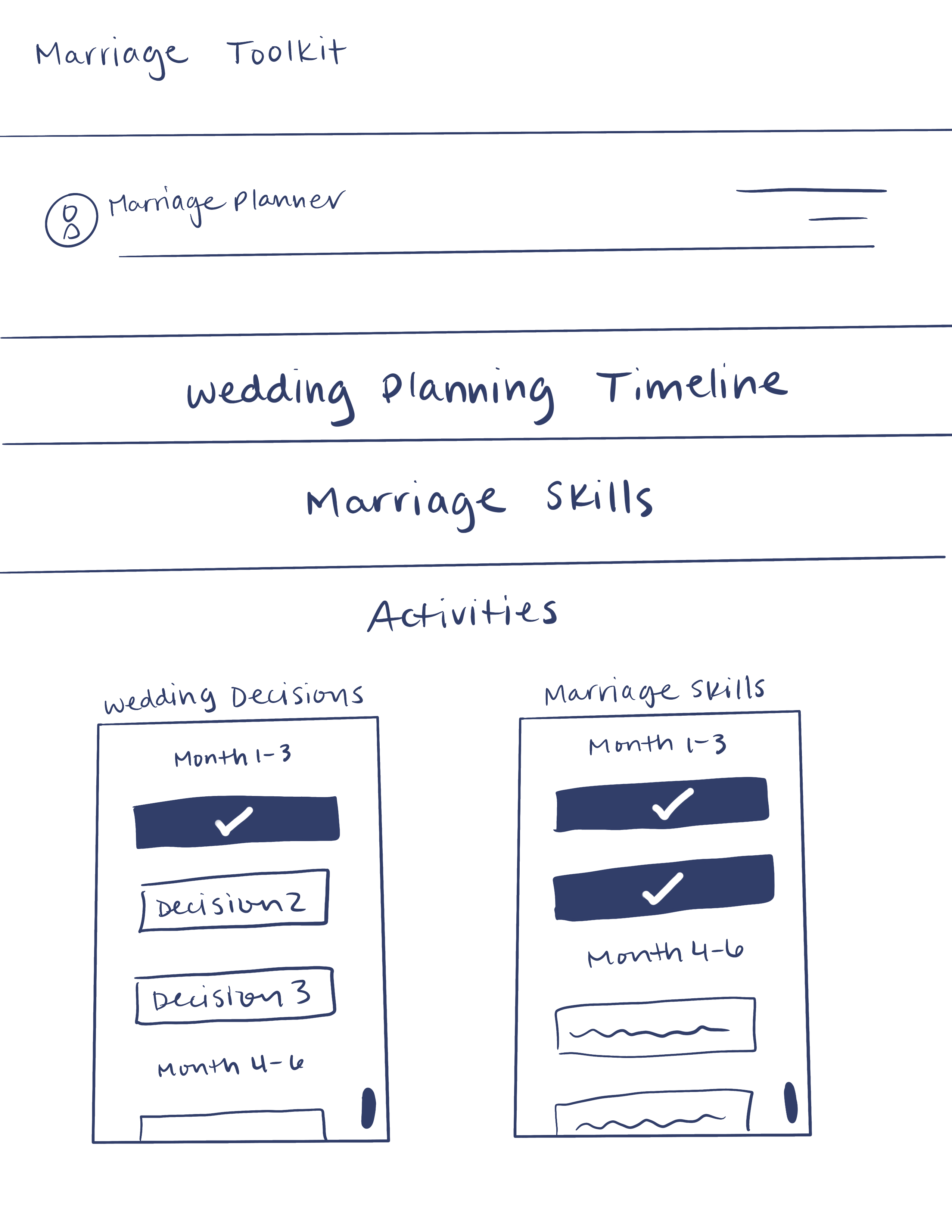

First I had them complete a card sort activity, which is an activity where users are given a list of topics related to the design and asked to organize them according to what makes the most sense to them. In the card sort I conducted, each partner separated the “Wedding Planning Timeline” and “Marriage Skills” sections, and they also added an “Activities” section that stored all activities from both sections in one place.

Next I had the couple complete a usability test, which is a test that evaluates ease of use by asking users to complete tasks while interacting with the design intervention. In the usability test, both partners had issues during the “About You” Questionnaire and the Marriage Toolkit activities when there was more than one call to action. There was confusion about which buttons to press. The male participant also said that he liked the design of the Marriage Toolkit but found it a little overwhelming to look at.

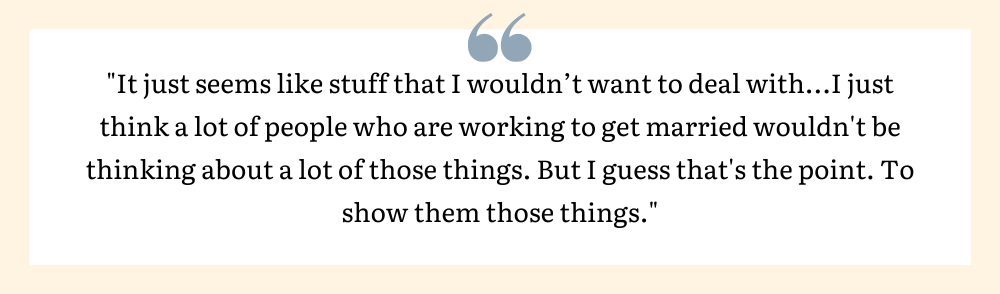

The last thing I did was conduct an interview with the couple. When asked about the overall usefulness of the website, the male participant said he wouldn’t find the app useful and that he didn’t think other couples would, either.

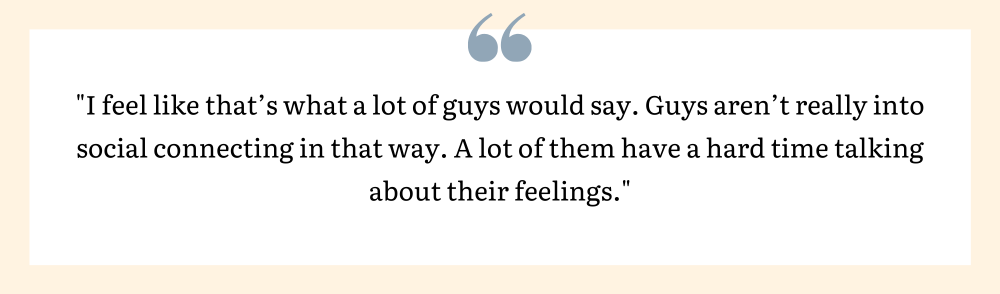

While I was recovering from the small blow to my ego he went on to say that he recognized a reason or the design even if he wasn’t particularly interested in it. Then the female participant quipped with a comment about how that kind of response is expected from men.

Both partners said they liked the questionnaire and the activities. They liked the questionnaire because they felt it asked questions that said a lot about a person even though it consisted of all multiple choice questions. The male participant said that he would have liked to have seen more abstract open-ended questions to get more personal insights, and the female participant said that she would have liked to have been able to elaborate on her answers with open-ended responses.

Both partners also liked the activities because of how easily they could be applied to real-life situations.

In regards to the marriage coach, both partners were less impressed. They said that while they liked the ability to see a video of the marriage coach speaking because it would give them a glimpse of their compatibility with the marriage coach, they still wouldn’t seek advice from a stranger unless they had credentials in that area. The male participant said that he would have liked to have seen a training process. The female participant agreed and said that she also would have liked to have seen more personal interaction because she would feel more comfortable talking to someone she knew more intimately.

Conclusions

Given the small testing sample size, it’s hard to say whether Marriage Planner is successful or not, but there seem to be both positive and negative responses to specific elements. The questionnaire and activities were positively received by the couple because of their usefulness in interpersonal learning and real-world application. The marriage coach, however, lacked necessary credentials and social intimacy to be considered valuable.

Suggestions for Future Design

Results from the prototype testing show a need for design revisions. The first thing I would do is create a more personal or intimate environment by including more open-ended questions in the questionnaire and marriage coach profiles. This would help the partners and coaches learn more about each other and build a stronger foundation for trust.

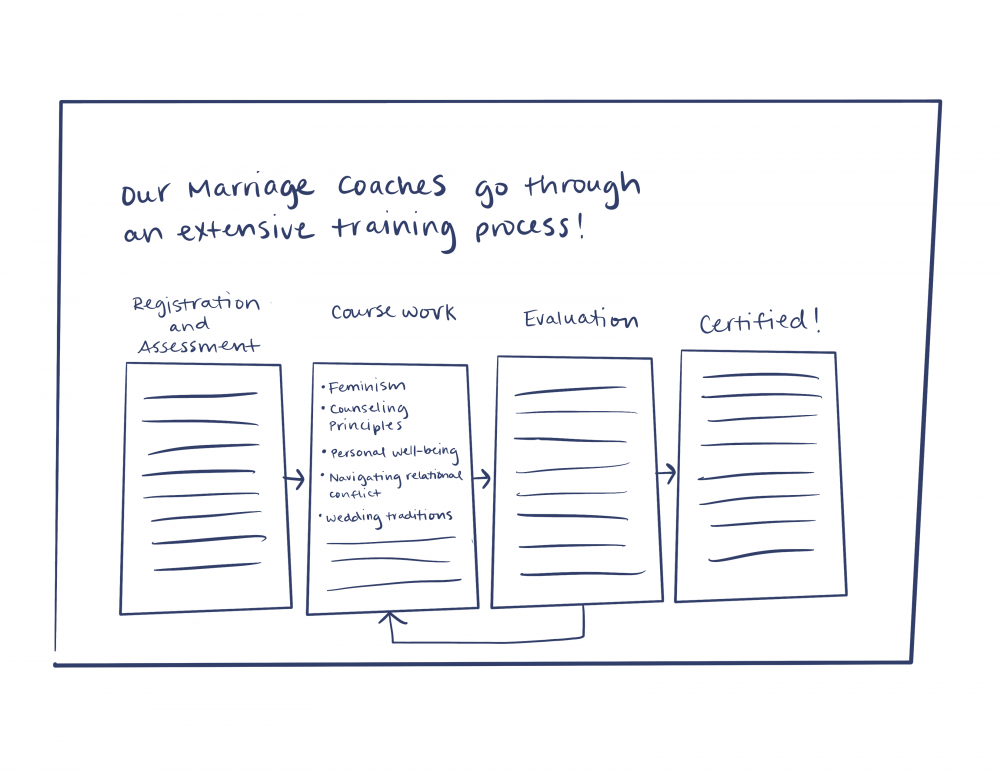

The next thing that I would do is advertise the training process of the marriage coaches to highlight their qualifications and credentials for their position. I would demonstrate this on the homepage by breaking down each phase of the training process and emphasizing the evaluation and revaluation requirements before the coaches could be certified.

The last thing I would do is separate the “Wedding Planning Timeline” and “Marriage Skills” section into two expandable sections rather than having all of the information overwhelmingly displayed on one page. I would also add an “Activities” panel in this section so couples could see all of their activities in one place and keep track of the completed ones.

Sketch of Marriage Planner Revision of Marriage Toolkit 1.

Sketch of Marriage Planner Revision of Marriage Toolkit 2.

Sketch of Marriage Planner Revision of Marriage Toolkit 3.

Sketch of Marriage Planner Revision of Marriage Toolkit 4.

Suggestions for Future Research

I suspect that engaged Christian couples who haven’t previously been married might not recognize a need for a service like Marriage Planner because of unrealistic expectations. For couples to want to sign up for a social counseling-style service, research would need to be conducted to find out more about how engaged couples’ unrealistic expectations about weddings and marriage make them unaware and unprepared to tackle relationship conflict. Most of my prior research studied the opinions of women, however, much of my prototype testing results addressed a male opinion. Additional research should be conducted to study how men view relationship conflict and sexist attitudes and how an intervention could be designed to motivate men to engage in constructive conflict behaviors.

References

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge. http://lauragonzalez.com/TC/BUTLER_gender_trouble.pdf

Canary, D J., Cupach, W. R. & Messman, S. (1995) Relationship Conflict: Conflict in Parent-Child, Friendship, and Romantic Relationships. SAGE Publications.

Coontz, S. (2006). Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage. Penguin Press.

Engstrom, E. (2012). The Bride Factory: Mass Media Portrayals of Women and Weddings. Peter Lang Publishing.

Engstrom, E. (2008). Unraveling The Knot: Political Economy and Cultural Hegemony in Wedding Media. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859907306833

Erickson, M. J. (2013). Christian Theology. Baker Academic.

Fairchild, E. (2013). Examining Wedding Rituals through a Multidimensional Gender Lens: The Analytic Importance of Attending to (In)consistency. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 43(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241613497750

Friedan, B. (1963). The Feminine Mystique. W. W. Norton & Company.

Gendler, A. (2014). The History of Marriage. TEDed. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-history-of-marriage-alex-gendler#watch

Humble, A. M., Zvonkovic, A. M. & Walker, A. J. (2008) “The Royal We”: Gender Ideology, Display, and Assessment in Wedding Work. Journal of Family Issues. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0192513X07305900

Kalmijn, M. (2014). Marriage Rituals as Reinforcers of Role Transitions: An Analysis of Weddings in The Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and Family.

Knee, C. R., Lonsbary, C. & Canevello, A. (2005). Self-Determination and Conflict in Romantic Relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 997-1009.

Livingston, G. & Brown, A. (2017). Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. Virginia. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/05/18/intermarriage-in-the-u-s-50-years-after-loving-v-virginia/

Martos, J. & Hegy, P. (1998). Equal at the Creation: Sexism, Society, and Christian Thought. University of Toronto Press.

Maltby, L. E.; Hall, M. E. L.; Anderson, T. L. & Edwards, K. (2010). Religion and Sexism: The Moderating Role of Participant Gender. Sex Roles, 62, 615-622.

Murphy, C. (2015). Interfaith Marriage is Common in U.S., Particularly Among the Recently Wed. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/02/interfaith-marriage/

Nicholson, L. (1997). The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory. Routledge.

Parker, K., Graf, N. & Igielnik, R. (2019). Generation Z Looks a Lot Like Millennials on Key Social and Political Issues. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/01/17/generation-z-looks-a-lot-like-millennials-on-key-social-and-political-issues/#gen-z-and-millennials-have-similar-views-on-gender-and-family

Pew Research Center. (2014). Divorced or Separated Adults. Pew Research Center: Religion and Public Life. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/marital-status/divorcedseparated/

Ruether, R. R. (1993). Sexism and God-talk: Toward a Feminist Theology. Beacon Press.

Reuther, R. R. (2014). Sexism and Misogyny in the Christian Tradition: Liberating Alternatives. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 34, 83-94.

Simon, V. A., Kobielski, S. J. & Martin, S. (2008). Conflict Beliefs, Goals, and Behavior in Romantic Relationships During Late Adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(3), 324-335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9264-5

Sniezek, T. (2005). Is It Our Day or the Bride’s Day? The Division of Wedding Labor and Its Meaning for Couples. Qualitative Sociology, 28(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11133-005-6368-7

Stepler, R. (2017). Number of U.S. adults Cohabiting with a Partner Continues to Rise, Especially Among Those 50 and Older. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/06/number-of-u-s-adults-cohabiting-with-a-partner-continues-to-rise-especially-among-those-50-and-older/

Support for Same-Sex Marriage Grows, Even Among Groups That Had Been Skeptical. (2017). Pew Research Center. Retrieved October, 2019, from https://www.people-press.org/2017/06/26/support-for-same-sex-marriage-grows-even-among-groups-that-had-been-skeptical/

Tong, R. (2001). Feminist Theory. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 5484-5491. Pergamon. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03945-0

Tyson, L. (2006). Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide. Routledge.

Zeff, L, & ABC News Productions for the History Channel (Producers). (2002). XY Factory: A History of the Wife [Motion picture]. United States: A & E Television Network. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=01OFk3DSwR4

OhioLINK Access

xdMFA Candidates must disseminate their research online in the Ohio Library and Information Network (OhioLINK) Electronic Theses and Dissertations repository. This thesis may be accessed at http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=miami1588331262095651